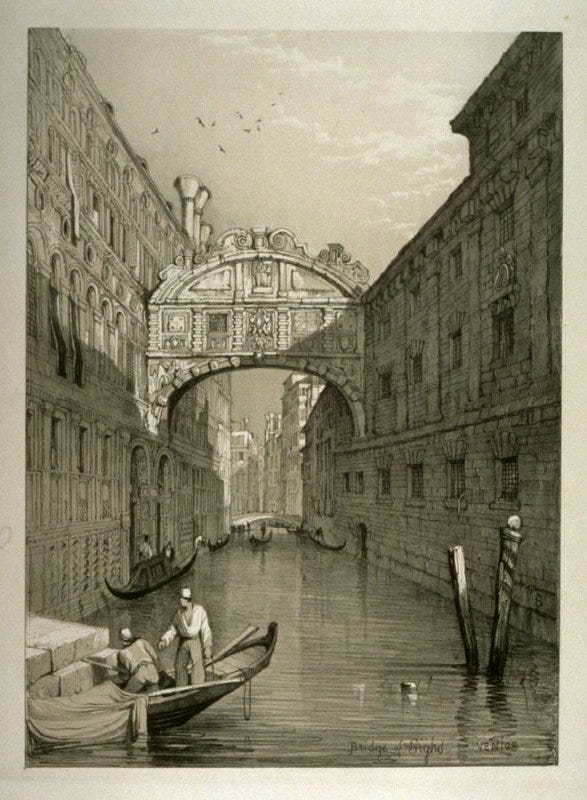

A Study of Schiller’s The Ghost SeerBy Cynthia Chung[THE AUDIO VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE CAN BE LISTENED TO HERE.]The Ghost Seer first appeared in several instalments in Schiller’s publication journal Thalia from 1787 to 1789, and was later published as a three-volume book. It was one of the most popular works of Schiller’s during his lifetime. People were attracted by the subject of mysticism, apparitions and the horrifying unknown. It is for this very reason, that the Ghost Seer is actually one of the most misunderstood stories by Schiller, who was not only intervening on such peaked interests of the time but, more importantly, was meant as a warning for those who mistook a real villain for something that could only exist in the mysterious ghoulish world of the supernatural. Before we go further in elaborating on this, I think it is important that we first have some context of the environment that Schiller has chosen to tell this tale. The story is set without specifics, that is we don’t know the exact year or names of persons since the story is being told by a character named Count O (we are only given the first letter of his name) who has chosen to leave out these details, and we are told that the story is set sometime in the 1700s in Venice. Since the entire story is set within Venice, I think it important that we know about what kind of city Venice was. Venice, for all its influence, wealth and power, was contained on a small little island in the lagoons and marshes of the northern Adriatic Sea. It was founded through an emigration of leading Roman families after the western empire’s collapse around 700 AD. Venice did not have a strong or large naval defense. Rather their most efficient defense was the fact that they were located in the middle of a swamp. Not only this, but Venice was rather adept in the art of espionage and was a center for the highest level of intelligence gathering within Europe. This allowed them to frequently have the upper hand in manipulating foreign policy. In addition, Venice was a very powerful banking center of Europe. The Venetian bankers, often called Lombards, began to loot many parts of Europe with usurious loans at 120-180% interest. In 1345, the biggest financial crash in history hit Europe. The Venetian controlled Peruzzi and Bardi family banks had overextended themselves in loans, primarily to King Edward III in his cause against the French which would end up as the ‘Hundred Years War’, when King Edward III repudiated his war debts in 1343 to all foreign banks, the already overly-extended Bardi and Peruzzi banks could not sustain themselves for much longer and in 1345 led Europe into what would become the peak period of the dark age. The oligarchical families in Venice would become extremely rich off of this system, and stored much of their family fortune, called the fondo, within the Basilica of St. Mark, which functioned like a Venetian state treasury and would absorb the family fortunes of nobles who died without heirs. It was fairly frequent in Venice that nobles would die under mysterious circumstances or be assumed dead but the body never found. The canals of Venice were well known for being full of such bodies, which the murky water kept hidden for the most part. The best way to understand Venice, was that its power was centered in pitting their enemies against each other. Venice had developed such a reputation for this that by 1508, there would be an agreement between France, Spain, Germany, the Papacy, Milan, Florence, Savoy, Mantua, Ferrara and others to form a league to dismember Venice, called the League of Cambrai. Unfortunately, Venice was conniving enough to corrupt certain members of this league with the promises of massive wealth and influence such that just as the league had the fate of Venice in its hands, its members started to turn on each other and Venice survived. It is important for us to especially understand as it is one of the main themes of the Ghost Seer, the outlook of the free thinker, represented by the spirituali. The free thinkers are Aristotelian based, and hold the belief that reason lies in the methodology of logically based induction and deduction. That the universe is a mechanism, discoverable by a few simple laws. Free thinkers, which ultimately shaped the period known as the Enlightenment, emphasized individualism, skepticism and ‘science’ reduced to the confines of empiricism and agnosticism. This school of thought was in direct opposition to the Platonic school, which characterised the Renaissance as a cultural intellectual movement known as platonic humanism. Platonic humanism would revive the study of ancient Greek and Roman thought. It began and achieved fruition first in Italy, and its predecessors, were such men as Dante and Petrarch. Renaissance humanism had set out to help humankind break free from the mental strictures imposed by religious orthodoxy and to inspire instead free inquiry and criticism and a new confidence in the possibilities of human thought and its potential creations. Though timelines like this are common in classrooms today they grossly misrepresent how ideas have and will shape our past, present and future. An idea never just dies on a certain date, but rather can go through countless rebirths. Those who upheld the principles of renaissance humanism, or platonic humanism didn’t just all decide to become a free-thinker, or an aristotelean humanist after a certain date. As we can see from the use still today to describe them as either platonic or aristotelean this opposition between these two schools of thought has existed for centuries. In fact, Florence to this day has remained a Renaissance based city and Venice the base of the Enlightenment. What was this opposition between both schools? Centrally, it is on Aristotle’s assertion that slavery is a necessary institution, as he clearly expresses in his Politics:

Aristotle also reduced the question of human knowledge to the crudest sense certainty and perception of “facts” as he also showcases in the above statement, in his approach to the justification of slavery as a “fact”. From this sour core stems all of its pestilent growths in its philosophical shapings. It was Dante and Petrarch who laid the basis for the Italian Renaissance in the midst of the crisis in the 1300s. This effort was continued by Nicolaus of Cusa, Pope Pius II, and the Medici-sponsored Council of Florence in 1439. Counter to this, the Venetians promoted the philosophy of Aristotle against the Platonism of the Florentines, and the University of Padua became the great European center for Aristotelian studies. Pius II, who was Pope from 1458-1464, was an ally of Nicolas of Cusa and the platonic humanist movement. He would help Cusa in organising the Council of Florence (1431-1449) as an attempt to unite the eastern and western churches. [In Webster Tarpley’s article “Venice’s War Against Western Civilization,” he goes through in-depth in his research why this is the case using the following quotes.] Pius II had said of the Venetians:

Though the League of Cambrai ultimately failed, it came very close to destroying Venice and Venice suffered greatly financially as a result. As a reaction to this, a decision was made by Venetian intelligence to pit Protestants and Catholics against each other. The goal was to divide Europe for centuries in religious wars that would prevent any combination like the League of Cambrai from ever again being assembled against Venice. Gasparo Contarini was a cardinal based in Venice during this time. He was a pupil of the Aristotelean Padua school, and denied the immortality of the human soul. According to Tarpley’s research, in 1943 an interesting find was made by a German scholar named Hubert Jedin within the Camaldolese monastery of Monte Corona…30 letters from Gasparo Contarini that show without a doubt that Contarini was organising Protestant circles in Italy despite being a Catholic and a cardinal at that. In other words, he was caught fanning the fire from both sides. As is well-known, Martin Luther is responsible for the formation of Protestantism in 1517 which was launched in Germany. To give us an idea of why this is relevant to Venice’s design let us read an excerpt from Contarini. When he returned to Venice in 1525 from his mission with Charles V in Germany, he told the Senate:

Venetian publishing houses and networks would now work to spread Lutheranism and its variants all over Germany in order to perpetuate and exacerbate these divisions. As stated in Webster Tarpley’s article “Venice’s War vs Western Civilization“:

Contarini would die in 1542, before these divsions became pronounced. In 1536, Paul III would select Contarini to chair a commission that would develop ways to reform the church. Besides Contarini would be Caraffa, Sadoleto, Pole, Giberti, Cortese of San Giorgio Maggiore on the commission, an overwhelmingly Venetian selection. This report was titled the Consilium de Emendenda Ecclesia, and would focus on the abuses within the Catholic church. Two excerpts from this report give us an idea of what these Venetians had in mind for the restructural reform of the Catholic church.

Thus, Aristotle’s spirit was to head this “reform of the church” and would lead into the Council of Trent campaign. Erasmus was the leading platonic humanist of his day, and his mention in the report was not by chance. The Index Librorum Prohibitorum would form as a consequence of this report, and its lists of forbidden books, which were judged to be dangerous to the faith and morals of Roman Catholics, had a suspicious gravitation towards works by platonic humanists. Among the banned works would include those of Dante, Erasmus and all of Machiavelli’s books. This meant that the Aristotelians now held power in Rome. By 1565, there were no fewer than seven Venetian cardinals, one of the largest if not the largest national caucus. According to Tarpley’s work, after 1582 the oligarchical Venetian government institutions were controlled by the giovani, and the intelligence circle titled the Ridotto Morosini would form out of this. A leading member of this circle included a Servite monk named Paolo Sarpi. The giovani were interested in forming France, Holland, Protestant Germany, and England as a grouping counter to the Diacatholicon (Spain, Italy and the papacy). Out of the Ridotto Morosini Venetian intelligence circle would come the French Enlightenment, British empiricism, and the Thirty Years’ War. Here are a couple of quotes by Sarpi to give us an idea of his philosophy and character. He thought of man as a creature of appetites and that these appetites were insatiable, he wrote in his Pensiero, “We are always acquiring happiness, we have never acquired it and never will.” He would also write in his Pensiero:

This was simply a re-packaged version of the epistemology of Aristotle, which formed the foundation of thought governing the giovani, and is here represented by their follower, Sarpi. Such a belief formed in its adherents skepticism of anything good and beautiful. They were instead to fill this vacuum with a contempt for man and for human reason. Sarpi for instance made no secret that he thought of man as the most imperfect of animals. Sarpi’s intelligence circles went into action to create the preconditions for the Thirty Years war, not in Italy, but in Germany. The first step was to organize Germany into two armed camps. First came the creation of the Protestant Union of 1608 and within a year a Catholic League was formed, and the stage for a bloodbath was set. The papal nuncio in Paris reported on March 3, 1609 to Pope Paul V on the activities of the Venetian ambassador, Antonio Foscarini, a close associate of Sarpi:

The Thirty Years War (1618-1648) would be instigated from this, pitting the Protestants and Catholics against each other in one of the most destructive wars in human history. Germany would lose 1/3 of its population. Machiavelli was at the center of the fight to destroy Venice and played a large role in helping organise the League of Cambrai. He has received an ill-repute due to his writing The Prince, which is in fact a study of Venetian strategy, something Machiavelli knew could only be defeated if one understood the nature of such an enemy. Venice’s greatest weapon was its ability to manipulate the perspective and motives of its targets. They did not engage in military warfare but rather a mental warfare which most were seriously under-equipped to defend themselves against. The Prince was thus written by Machiavelli as a study of the enemy’s mind in order to defend the humanist base in Florence. It was written specifically for Lorenzo de Medici who would become the ruler of the Florentine Republic. Lorenzo was a very powerful and enthusiastic patron of the Renaissance culture of Italy. Let us look at the final paragraph of Machiavelli’s The Prince to gain further insight into this battle:

The tragedy of wars such as the Thirty Years war was very much on the mind of Schiller. How could brother be pitted against brother with such vehement hate? How could one allow themselves to be so completely manipulated, so easily fooled into believing an absurdity, into believing that a friend was actually a foe? Most wars are the result of such methods, and therefore Schiller thought it of the utmost importance that the people, but most especially its leaders come to understand the mind of such villainy. That once recognised and exposed for what it truly is, it would lose much of its influence, and good people would no longer be manipulated by such machinations. With this in mind we are now prepared to embark on Schiller’s Ghost Seer tale. You can think in a way that this story is like one long magic trick and it is important that you keep your mind focused on what is really occurring rather than on the flourish and distraction. Otherwise you will mistake the deed for real magic when in actuality it was all a series of slight of hand. The Ghost Seer Book IWe are going to start off at the beginning of the story. Count O is the narrator and is recounting his experience with his friend, a prince from a German territory, who was staying in Venice at the time. Count O is visiting him on the way to his destination and they decide to remain together in Venice for a few days before the prince’s departure back to Germany. Count O starts his narration off by giving his reasons for re-telling this story and thus proceeds to describe the character of his friend the prince.

The prince lived incognito. He kept his distance from diversions and had resisted all of the enticements of this city of temptation. Being the third prince of his house, there was hardly any prospect that he would rule one day. He was Protestant by birth albeit his convictions were not the result of inquiries; these he had never made.

One night, during an evening stroll both the prince and Count O notice that they are being followed. They know of no reason for this, and sit at a bench hoping it is possibly just a mistaken identity. The Armenian following them, sits at an adjacent bench and just as the prince gets up and exclaims to the Count that they should be leaving since they need to arrive at their destination by 9 pm, the Armenian responds “He died at 9 o’clock.” The prince and Count are stricken by this ominous person and leave for their hotel immediately. A week passes by and the prince receives a letter, as he is strolling through the city, confirming that his cousin, who is first in line for the crown, did in fact die last thursday evening….at 9 o’clock! At this moment, the Armenian emerges from the crowd and tells the prince that he urgently needs to meet with the deputies from the senate. Once the prince returns from this mysterious meeting, whom the Count did not accompany him to, the prince says to the Count:

The prince already at this early stage has developed an obsession with how the Armenian’s mysterious prediction came true and has referred to his own possible ascension to the throne as a trivial matter! It is interesting that Schiller has the prince use a Hamlet reference. What was the ultimate tragedy of Hamlet? Hamlet became obsessed with a ghost, he put the importance of this phantom above everything else. Hamlet did not think of his role as a better king that was needed to end the mayhem and ensure the security of Denmark. When Hamlet discovered that his uncle was guilty of the murder of his father, he continues inaction. By the end of the play Hamlet has never made any real decision or action in order to determine his own fate, let alone the people of Denmark. He lived more in his head than in reality. He does end with killing his uncle, but only after everything is lost. After all possible avenues of action are already destroyed and his own death certain, only then does he finally kill his uncle…but there is no one left to govern and the people of Denmark are lost. Refer to my lecture on this subject for more detail. The prince very evidently does not wish this responsibility to rule. He has never prepared himself for this role, thinking it would never be his. And he confesses that he would rather become a monk, an isolated figure with no heavy expectation, than a king. The next evening, the prince is playing cards with a group of people, he ends up getting into an argument with a Venetian and insults him. The commotion is so loud, that the Count enters the room and yells “Prince!”. Recall that nobody knew of the prince’s identity up until this point. As soon as the Count revealed his identity, half of the room went empty and the remaining were all attempting to offer the prince help in the situation he got himself into. They warned him that this Venetian would surely have him killed tonight and started to compete with one another as to who would be chosen to help the prince. The prince and the Count end up leaving the place on their own and decide to head straight back for their hotel. Along their way, they are ushered forcefully into a gondola by a group of people and are taken to a dark building, led up a winding staircase where they enter a room…

The prince, would have from this point on, protection bestowed on him by the highest echelons in Venice. His identity was known and they wanted him kept in their safe keeping. At this point it seems all of Venice is aware of the prince’s identity and he quickly gains an entourage. One evening his entourage follows him into a hotel for dinner. During the dinner the prince gushes over the mysterious Armenian and his eerie foretelling of the death of his cousin on its exact hour. The conversation quickly becomes focused on whether the supernatural does indeed exist. At this point, a Sicilian magician in their company offers his “skills” in settling the matter.

It is interesting to note here, that the prince has a more ready tendency to accept that he has a special selection in the sacred/secret sciences in the supernatural rather than his selection as a king, a future leader of a people. He thinks he can be one of the few who can be taught in the art of the “sacred sciences”, that he possesses the rare qualities for “initiation”. The word mysticism is derived from Greek, and its original meaning is “to conceal”. Its derivative is mystikos, meaning “an initiate”. In the Hellenistic world, the word mystical referred to “secret” religious rituals. A “mystikos” was, therefore, an initiate of a mystery religion. The word mystery has its root from mystikos, and refers to revealing truths that surpass the powers of natural reason, in other words, the root of the word mystery can be understood as a truth that transcends the created intellect. Already it is evident that the prince does not think he can come to understand the highest mysteries as a discovery through reason, but rather he thinks these mysteries will unfold themselves to him if he is chosen to be initiated, if he is allowed entry into this enchanted, mystical realm. A seance is organised for that night. The prince has selected to conjure up a friend of his who was killed in battle. The magician needs several hours to prepare and in the meantime about half the entourage remains in anticipation, among these are a British man and a Russian. Finally, it is time for the conjuring. They enter a darkly lit room, the magician says his incantations and suddenly an image of what seems to be a spirit appears in the background. However, as soon as this apparition appears, a second apparition seemingly of the same ghost also appears and is much closer to the spectators and much more real! The prince himself is amazed at the likeness of this ghost to his long past-away friend. The magician appears frightful and turns pale at the appearance of this second apparition and falls to his knees. The Russian in their company then growls at the magician and says “You shall never conjure spirits again!”. The magician looks into the face of the Russian and seems to recognise him, he screams in horror and faints. Immediately following this scene, guards enter and arrest the magician. The Russian is seen speaking to them and arranges for no one else in their party to be arrested. At this point it is revealed, that the Russian was in fact the Armenian in disguise. Amongst all the clamour, the Armenian is nowhere to be found, the prince wants to go searching for him and remarks:

And a few paragraphs later…

Notice how the prince is convinced that someone or something with so much evident power cannot possibly be human. Anything so awesomely mysterious and powerful must be from the supernatural realm. The next day the prince, the Count and the British man decide to see the magician in his prison cell in an attempt to try to get some answers from him.

The prince is now very much embarrassed to having taken so seriously something that has so clearly been proven a fraud. However, observe that the magician never answered a purpose to the design… The prince then questions the magician as to why he was so horrified upon recognising the face of the Armenian during the seance, where did he know him from? The magician then goes on to recount a story of his first encounter with the Armenian. It started with the tragedy of a well off family who’s first son had gone missing. The family had searched in vain for years and a body was never recovered. The first son was to have been married to the daughter of another family, they were very much in love and both families had been holding off her marriage to anyone else hoping for his return. It is upon this scene that the magician is hired into their company:

It is accepted by the family that a seance should occur in an attempt to speak to the first son’s phantom, if he is in fact dead.

In other words, people are not suspicious of supernatural explanations because it is beyond understanding, it is beyond reason. Therefore if they can be convinced that they saw something partaking in the mystical, that is all the conviction they need. They only need be convinced by their senses, the mind plays no role in this domain since it is not something that can be rationalised. As soon as the illusion or effect appears more natural than supernatural, our mind is engaged and takes over. Therefore, if you were a fraudster like the magician, nothing would be more dangerous than to allow someone’s mind to turn on. The prince ironically fully agrees with this. The story of the magician ends with a wedding ceremony of the second son with the daughter that was destined to be betrothed to the first son. Since the family has had closure from the seance and ‘confirmation’ that their first son is truly gone, they decide to move on. At the wedding, the magician sees for the first time the Armenian, dressed as a Franciscan monk, as he shouts out in the middle of the king’s speech “May I ask why you have not invited your first son to this wedding?”. The king responds that he is gone where one remains for eternity. The Armenian responds “Maybe he only fears to show himself in such company. Let him hear the last voice he ever heard. Ask your son Lorenzo to call for him.” There is confusion amongst the wedding party, the king chooses to be unaffected and raises his glass and gives a toast to the memory of his first son. Everyone is seen to drink out of their glass except Lorenzo (the second son). The king beckons him on and Lorenzo accepts the glass of wine offered to him from the Armenian, he drinks hesitantly as he says “to my beloved brother”. At this point the phantom of the first son appears and says “That is the voice of my murderer.” Upon this Lorenzo is seen in the throes of death and starts to convulse violently. The magician claims to have no further details of the event because at this point he had fainted. He adds that the prince did shortly after die and the only ones to attend him, his father and the priest died within a few weeks after. In addition, there was a skeleton found hidden amongst foliage on the castle grounds, and the second son for the seance had a ring of his brother in his possession that he offered for the fake conjuring of his brother. All these signs seemed to point to Lorenzo being the killer of his brother and suspicion as to what role the magician played in the affair. And so the story of the magician ends. The prince and the count leave with more questions than answers as to the identity and nature of the Armenian. After the magician’s answers, the prince feels disgusted, that this pure world of the sacred sciences, of the mystical world beyond our own has been sullied by such a good for nothing fraudster. He is also deeply embarrassed that he fell so hard for the whole affair. This disgust seems at first to have lifted the prince out of his dream state and awakens him to explain mechanically how every “trick” could have been done without magic up to this point. That it was all simply a series of cons. What seems to be a moment of clarity turns out to be a cold detached logic to the whole series of very odd events. And it all falls apart when the intention, the purpose of the whole intricate affair remains hidden. The prince even goes so far as to acknowledge that the Armenian has an important plan that the prince is either a target of or a means to an end but then throws this possibility quickly away.

The prince never fathomed or brought into consideration that this whole series of events could have been orchestrated by a true villainy within Venice that was focused on the prince for a very exact purpose. The purpose was never suspected by the prince for why would anyone go through the trouble of weaving such a series of very odd and intricate events just to toy with the prince’s mind? Such a thing was really unfathomable and thus it was never understood and an evil motive was never suspected. It always partook more in the illusion of something supernatural than of something with a human intention. As a result, now the prince’s belief in the eternal, in the laws ordering the universe have been shattered as a result of his belief in miracles being shattered. Due to his inability to explain mechanically, like he did with the other cons, how the Armenian was able to make his first chilling prediction, the prince concludes that it can all be explained rather by the mere random collisions of chance. The prince has given up on understanding what has been occurring around him, and thus at this point, he surrenders himself almost completely to his fate being chosen for him by what he mistakenly identifies as chance, but in fact is a villainy that has remained hidden from him. The prince has simply replaced his belief in miracles and relegated them to random chance. A rather artificial substitute for the same effect. The prince has gained confidence by crediting himself with identifying the fraud. However, it is a fraud that chose to reveal itself to him.

At the end of Part I we are left off with the Count remarking that not everyone could withstand what the prince had already undergone from such a hidden villainy, and that we should remain aware that most of us have not had our reason tested from such a formidable challenge, and that we would not, for the most part, even fare so well as the prince thus far. Nonetheless, the prince did ultimately succumb to this villainy, and the tale narrated by the Count is delivered more as a warning to those in the future since the fate of the prince by now has already been finalised and his tragedy fulfilled, having already ascended the throne through crime… Book II starts off with the Count summarising the changes in the prince’s character after the culmination of very odd events that have managed to successfully challenge the prince’s epistemology, though never with any realised intended purpose or intention as to why these events had occurred to him in such close timing to one another. Book II

The prince had originally a belief in morality and purpose that was founded upon his oppressive education in religious studies. He thought he had escaped this environment which suffocated all creativity, optimism and happiness. He thought himself free but had escaped with his chains. What were those chains? That he was never able to form an independent discovery of the nature of morality, goodness, or purpose outside of ultimately what were things he was taught to obey with blind faith. The prince was very much affected by his mystical beliefs which, unbeknownst to him, if they were to be utterly destroyed, he would have nothing to replace them with that could continue to uphold his foundation for morality and purpose. As Schiller stated; the prince’s convictions were not on firm foundation, and thus such a foundation was easily put into question, and the whole thing could come crumbling down with the discovery of one inconsistency. The prince was confronted with a string of experiences that shattered his belief in something beyond this world, something larger than us, and thus he lost all belief of its existence, when in fact he just didn’t base his belief on these matters appropriately, as Schiller used the example of one who is deceived in love or friendship and thus denies their existence, when in fact the error was in the misidentification of such a person partaking in such noble qualities.

The Bucentauro was made up of very important Venetian men, not only statesmen but cardinals, which very much impresses the prince at first. However, our earlier review of the historical role that Venetian cardinals played in geopolitics should give us insight into what sort of closed society this in fact was, and that the prince had walked rather into a den of snakes than so called “enlightened” thinkers. The prince thinks that these Venetian cardinals partake in the divine, but Schiller makes the point that people in these types of positions find no reins, they are at the top of the authority of what is deemed “moral”, and therefore the corruption at this level unfortunately is very high. Schiller makes the case, that a more typical criminal would feel some level of fear for the sanctity of their soul, however, with these sort of corrupt cardinals they are not concerned with such a fear, that is, they don’t actually believe in the immortality of the soul and thus are only worried with material consequences. They are in fact, not actually religious. And though they wear the robe of a cardinal, they actually revile their position and revile humanity. The prince has no insight into the nature of evil and thus is unable to recognise this at first. The prince discovers this partially but too late, and at that point he is even scared to leave this group, knowing they would heavily disapprove and would likely not allow such a thing to pass. Just being in contact with this closed society was enough to cause the prince to lose his “pure and beautiful innocence of character“. Quite powerful! For the prince did not have a strong intellectual foundation to place his moral beliefs on, but rather were free floating and instinctive for him. Thus, when he came across this impressive group of secretive high ranking men who had an astute mental rigour and were skilled in the art of sophistical argumentation, in other words the manipulation of the mind and its convictions, the prince’s innocence could not withstand the convictions they chose him to adopt. And he was reduced by the end of it “grabbing at the first arbitrary thing tossed at him.” What a sad position for a person to be in! Much of what follows in Book II I will not discuss in this paper since I think it very much follows in a straightforward manner from what we have already discussed in detail at this point. I also recommend that you actually take the time to read The Ghost Seer in its entirety. An online copy can be found here. However, what I would like to discuss in detail at this point, covers the section referred to as the philosophical dialogue within The Ghost Seer. The Philosophical DialogueThe philosophical dialogue section of the Ghost Seer is like a platonic dialogue except without Socrates. It is entirely up to the reader to guide themselves through the conversation. This is why this section is often forgotten about. It does not have steady ground for most people and thus it is not retained in the mind. Schiller actually made a point to extend the length of this discussion in later editions, knowing its central importance. In the philosophical dialogue the prince and his servant/friend the Baron are having a discussion on the nature and ordering of the universe and what role does humankind have to play in all of this. Count O has at this point returned to his homeland to manage an issue that arose there. Later Count O finds out that this was organised with the purpose of getting him to leave the side of the prince as he is further deconstructed in this Venetian spiderweb. The Baron is concerned over the prince’s sudden change in character since he has been in Venice and sees he has lost his belief in morality and a genuine goodness. Since this dialogue is somewhat challenging I have broken it up into what I believe to be its core themes so that we can discuss them more clearly. These are the central structural stones that Schiller identified as the bedrock for free thinkers, which we will discuss here and conclude what we make of them.

The prince never entirely believed in a benevolent God, as was discussed before, he had rather a love/hate relationship with a God he thought sometimes loving and sometimes wrathful. Now he has replaced that belief with a faceless, cold entity. In this cold alien world, we are nothing but material vessels for its will. It is not something that we can come to understand on any level, and these concepts of love and hate don’t have an intrinsic existence in this alien world. The question of our immortality in such a world is brought up by the Baron. The prince responds that anything material about us, including our desires which are shaped by the material (as per the prince) are extinguished after we die, therefore, what is there of us that could partake in the immortal? The prince goes on to state that it is his belief that this cold Nature has placed within us this impulse towards immortality such that we execute its will. This is best exemplified today by the theory of Richard Dawkins, who puts forth that any emotion or desire we have within us is ultimately dictated by our genes, and that these emotions and desires are not our own choosing but rather are designed for us to execute the “will” of the genes. The prince thus concludes that this impulse towards immortality is just an illusion and disappears along with the rest of us when our life is extinguished. The next subject of discussion turns to purpose, since obviously if you live in a world such as this, you cannot ultimately know a purpose in your life. To this the prince says…

As per the prince, the purpose of humanity is subject to the physical world, however, it is a purpose that we can never come to understand. We are guided towards the execution of this purpose by what Nature has instilled in us as pleasure and pain. That is, what Nature wills for us we are given pleasure by and what Nature abhors us to do is followed by pain. Thus pleasure becomes the greatest measure for good and pain becomes the greatest measure for the bad. However, this concept of bad does not have an evil intention or consciousness so to speak. You are thus in your highest execution of perfection if you allow yourself to be purely governed by pleasure. Whereas organic entities are constrained in their actions and completely beholden to Nature’s will through the laws of physics, such as the shape of a water droplet or that of a planet, where a water droplet or planet could not choose any other form for itself; humans are constrained and beholden to Nature’s will through the “laws” of emotion which keep us bounded according to our concept of pleasure and pain and we have just as much say in the matter as a water droplet does. “Thus, men need not be cognizant of the purpose which Nature carries out through them.” They simply only need follow pleasure and avoid pain. The prince then continues…

In other words, the eternal higher order of Nature does not have a mind, not at least a mind that we could in any way relate to or understand. It is not something that we can share or partake in. We are not the children so to speak of this entity. The Baron brings up the contradiction in the prince’s statement, that if we cannot know anything about the ordering or intention of this Nature how was the prince able to form even this extent in his understanding. Similar to those who claim “that there is no truth”, but are thus contradicting themselves in making such a statement and thinking it indeed a truth. The prince responds that he does not determine anything but “merely disregards what men have confused with Nature”. This obviously is not addressing the contradiction, since you cannot disregard something rightfully without some manner of insight as to why, which the prince does not give. The prince continues, that what preceded him and what will follow him are like two black impenetrable curtains, that is, the prince has this approach to the unknown that it is no different than if nothing occurred before him and nothing after him. There is no point in even trying to think about it because no mortal will ever be able to enter past those curtains.

So again using the example of Dawkins theory, if our will is really governed by our genes, the more successful we are in such actions, the more potent and superior must our genes be. And the more superior genes one contains within oneself, the more superior they will be in their cause for us to execute its will. The Baron then asks, but how do you differentiate between a superior and inferior action, what determines whether an action is good or bad? Isn’t there still a good and bad purpose behind such actions? And if not, isn’t moral beauty lost then? The prince responds “break your habit of presupposing that Nature organises itself from wholes“. That is, the prince does not believe in the universal, that things are ordered from top-down. He believes that we are just executions of parts and that we can’t ever know the intention of the whole, or if there is even such an intention. The prince continues that one can only assess the initial effect and not the chain of effects. And since we cannot know this chain of effects we cannot know its reason or purpose. The prince goes on to describe an example of two beggars, whereby the Baron gives a coin to one beggar who uses this to buy medicine for his ailing father and the prince gives a coin to another beggar who uses it to buy a weapon and commit murder, that despite the actions each beggar chose, the action of both the Baron and the prince are equal in effect. The prince continues “The effect of my act ceased to be my act with its immediacy“, that is, that the prince was only responsible for the action of giving a coin to a beggar and not for its outcome. The Baron then responds, but what if his intention in giving the coin to the beggar was for him to commit murder, wouldn’t the Baron then be responsible and isn’t it more a question of intention than the act itself? The prince then responds in a way which is quite the acrobatic feat in philosophy, that there is in fact no immediate connection regardless of intention, because “an entire series of arbitrary events will insert themselves in between each effect.” In other words, even if I give a coin to a beggar with the intention that they commit murder, there will be so many other separate actions and reactions in between the giving of the coin and the act of murder that will further reinforce or dissuade such an outcome from occurring. And thus, the prince concludes “you might as well admit at once that both acts are equivalent in their immediate effect” and an effect that occurs past the immediacy is not something that we can be held responsible for, thus we are morally indifferent to such outcomes as a coin being used to commit murder. And so the question of motive is brought up, and whether motive can even exist or have an effect as comprehended by such an outlook.

That is, if I am a moral person and I want to have a good intended effect but I fail at achieving such an effect, does this mean I am an immoral person? That is, is morality contingent on the success of the action or the intention? It is agreed by the Baron that morality is contingent on the intention, but not the success of the action. The prince goes on, since this is the case, we do not have to be concerned with the external world, the effects of our intentions, but rather let us focus on what internally organises our intentions. The prince then compares a moral being to a well functioning clock. And the more forces that are active within us, which is what Nature intended for us, the more perfect our function becomes, as in a clock. That is, if a clock is to work, it needs to have so many of its parts functioning, and the more parts that do not function in such a clock the less perfect its function or effect. The same goes for a person, as per the prince, that the more parts function, the greater the moral or good effect. Whereas, a bad effect is when the parts of a person cease to function in such a way that the generated effect is of a lower potency or force. Therefore a bad effect is the result of less forces potent or active within you, and therefore, is naturally inferior in effect relative to the good. With this approach the good will naturally have more potent forces active within itself and the bad less potent forces. Therefore, the bad is naturally inferior and cannot compete with the good. Looking at it from the standpoint of the prince, where does the concept of evil come into play? Well, we apparently need not concern ourselves with such matters since what Nature desires is for a good of sorts, that is, something that will exact its will that is unknown to us. With this understanding, the good is naturally superior as an accumulation of forces than the bad, and thus evil cannot play any governing role and we need not pay it attention. This showcases how incredibly naive the prince is, to presuppose evil as so inferior and so base that you need not concern yourself at all with it, especially in the context of being in the middle of a Venetian design for him! So how should we think of the nature of evil? St. Augustine offers one of the best answers that I have come across so far, to get at the crux of this question. It is not just a matter of being able to recognise evil, but it is also imperative that there is an understanding as to how the good is indeed superior, despite the nature of evil being so prevalent and seemingly powerful. In response to this, St. Augustine states that light exists on its own whereas darkness is in measured degrees an absence of light. What this means, is that when something partakes in an evil intention by utilising “creativity”, it has to borrow from the “light”, but manipulates and twists its form into something unnatural. This is why the nature of evil is inherently inferior, because it has to borrow from the good in order to have a powerful effect. This does not mean that evil is not incredibly dangerous, such as the case of what organised Venice as a political structure. However, if such a force of evil were to confront something that partakes in the highest good, it would not have the means to oppose it and the good would rule over it, since the good partakes in itself as an absolute. The problem with the prince’s philosophy, is that it is ultimately the philosophy of a slave. He thinks that he has somehow freed himself from his previous shackles and is his own sovereign now, but in fact he has become more enslaved then he has ever been in his life. He is enslaved because he denies purpose, and as soon as you deny purpose, you become the tool for someone else’s purpose. As soon as the prince was satisfied in explaining away the series of odd events that occurred to him as coming down to mere chance, including the eerie prediction of the Armenian as to the exact time of death of the prince’s cousin, who was next in line to be king, the prince gave up on these events being organised by a purpose. At that point on, the prince had blinded himself and could not predict anything sinister that was coming his way, but rather reduced himself to a position of taking things as they occurred to him. In other words, the prince’s fate was from that point on chosen for him and the prince removed his say in the matter by denying purpose. Let us now move onto the prince’s version of what is morality…

Again, according to the prince’s definition, a good act just has more forces in it and a bad act less forces active in it, so it is not necessarily a question of “evil”. But rather, that for whatever reason, you don’t have as many potent active forces within you to commit an act. So in this context, there really isn’t a bad per se but rather a hierarchy of more good and lesser good, and evil thus doesn’t really exist. The prince then goes on to give examples, that a person that does something that we deem despicable is not in fact doing something “bad” but rather chose a lesser force rather than a more potent force, such as ‘self-preservation” vs ‘courage’, or ‘bravery’ vs ‘justice’. And thus we only find the act despicable because they failed to act in the more magnificent force. Thus an action is “bad” because the greater, more magnificent forces did not act within you. From this same account, the prince concludes that a “bad” act is thus not an effect of a motive but rather the lack of a motive, in other words, it is not fulfilling its intended (by Nature) effect. This is equivalent to stating that it is not following Nature’s guide of pleasure, since pleasure as discussed earlier is the intended effect Nature desires from us, it is thus the greatest good and thus partakes in the highest morality, as per the prince. And thus, the person who has the most powers active within them must therefore possess the most excellent heart….

Remember, the prince doesn’t believe in the immortality of the soul, thus if you are to be rewarded for good actions they must be rewarded to you in the present. This whole idea of being moral but that your happiness is not necessarily an immediate reward to this is not the effect we see in Nature argues the prince. He goes to list examples: the blossom of a rose does not produce the pleasure of beauty a year later, it produces it in the now, the glow of the sun does not produce warmth a day later but in the now, therefore why should we expect it differently for a person who is self-contained, that is, that our morality is independent of what occurs outside of ourselves and therefore we should have happiness as an immediate effect. Thus pleasure is a measure of the greatest good according to the prince, since it produces an immediate reward. The Baron is unable to argue against this but he doesn’t agree with it, and states “and yet, this infinite pleasure, this feast of perfection, is supposed to stand empty for eternity!” The Baron recognises that what the prince has laid out as a measure for happiness is likened to one forever gorging one’s self and yet never feeling satisfied, to only know a feeling of hunger and never a feeling of satiety. Where is the fulfillment? The fulfillment is always fleeting in such an outlook. As Paolo Sarpi, a leading free thinker said, “we are always acquiring happiness, we have never acquired it and never will.“

Recall that the prince believes everything do be self-contained, such as a water droplet or the shape of a planet due to what Nature prescribes. In the case of non-living material, the law of gravity holds them within a self-contained boundary that they cannot exit from. The prince believes that a person is also a self-contained unit, whose boundary condition is prescribed from Nature not through gravity by rather the emotional desire for pleasure and avoidance of pain. Because everything is self-contained in this manner, as per the prince, immortality cannot exist since it would require an ability to exit such a material boundary condition. Thus the prince says that if he could only see a splinter jutting out of a beautiful circle proving it were not a self-contained form, if the prince could only witness such an imperfection that freed itself from its prescribed boundary, he could then believe in an immortality. But the prince concludes such an imperfection does not exist and thus immortality is nothing but an illusion, a dream. In order for us to be solid in our morality and sovereignty we need an acknowledged purpose, very specifically and essentially a purpose that is larger than us, far larger. Religion is the domain that tends to cover this subject most often. However, belief and faith in a purpose larger than us is not the same as knowing. Is it possible to know? Belief and faith that are essentially blind and doctrinal, that is, were adopted without a proper investigation into whether they are truthful, when such beliefs are shattered or disappoint there is nothing left to uphold our understanding of ourselves nor how we are situated in something that partakes in the eternal. In the case of the prince his belief was shattered and he became a free thinker, a believer in a cold world that wasn’t any more alive than if it were all made of crystal. He denies that the universe has a mind, but rather seeks its conception of perfection which is ultimately inconsequential to humans who live mortal lives within this cold sphere. He agrees that the condition of human happiness based off of pain and pleasure are tied to this but because it has no mind and it is instinctive within us, it rules us and whatever we feel or think is a consequence of nature’s will in us. The prince no longer believes in a truly moral purpose to anything in this world. He no longer believes in an immortality of the soul. We are moulded by nature in a temporal existence and wither away. Remark by the Count O:

Count O is stating here, that it was this philosophy of the prince which sealed his doom, and which would cause him to ascend the throne in crime. The rest of the story features the prince getting deconstructed further and further to the point where he becomes a complete slave to his senses. The story ends with Count O recounting how he rushed to meet the prince in Venice since he heard the prince was in a very bad situation:

So the story ends with the prince in a Catholic mass. Recall that the prince was a Protestant and must have been converted to Catholicism by the Armenian. Knowing the overview we made earlier on the Venetian orchestration of the Thirty Years War, it is finally revealed what the intended purpose for the prince was this entire time. The prince was to become an instrument in this pitting of Catholics against Protestants, and as Schiller remarked of the prince earlier, he would ascend his throne in crime. Recall that about 1/3 of the German population was killed as a result of the Thirty Years War. We can only imagine what sort of heinous crimes the prince later found himself caught up in, including most likely the annihilation of his Protestant court including his family and friends. So much for an orchestrating purpose never existing, as per the prince. Just like Hamlet, the prince ultimately never had any control over what happened to him or his people as a result of a flawed and rather self-contained viewpoint of oneself and the misunderstood consequences of ones action or rather inaction. The Rising Tide Foundation is a non-profit organization based in Montreal, Canada, focused on facilitating greater bridges between east and west while also providing a service that includes geopolitical analysis, research in the arts, philosophy, sciences and history. Consider supporting our work by subscribing to our substack page and Telegram channel at t.me/RisingTideFoundation. You're currently a free subscriber to Rising Tide Foundation. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Wednesday, October 18, 2023

Schiller’s Ghost Seer, Intelligence Methods and a Global Citizenry

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Matthew Ehret is coming to Calgary and hosting an event on March 29 (on the British Roots of the Deep State). And …

Hello everyone, ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Greetings everyone ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Rising Tide Foundation cross-posted a post from Matt Ehret's Insights Rising Tide Foundation Sep 25 · Rising Tide Foundation Come see M...

-

March 16 at 2pm Eastern Time ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

No comments:

Post a Comment