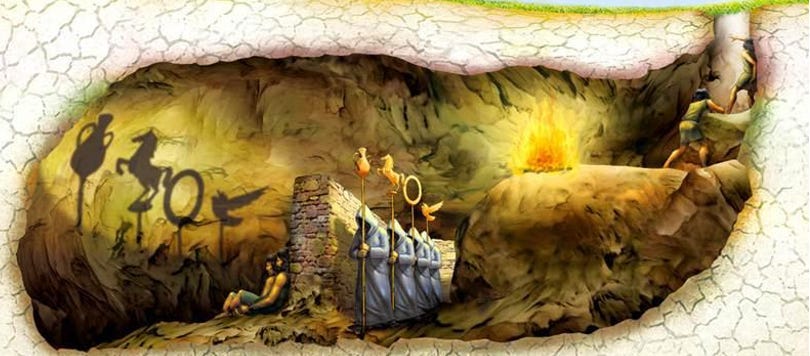

By Gerald Therrien (aka: A Canadian Yankee in King Arthur’s Court)While watching the decline and fall of today’s North Atlantean Empire, there seem to be many possible outcomes. One possible outcome is the complete destruction of this North Atlantean culture, and another possibility is the correction of this North Atlantean culture that will allow it to cooperate with the rest of the peoples of this planet for their common good. Although we were taught in school that among the British people there were (and are) many good English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish people, still that word ‘British’ always had a bad taste to it, because it reminded us of the ‘British Empire’. And I’ve often wondered, what part of our cultural heritage had to be suppressed, in order to get us, North Atlanteans, to go along with this modern form of the ‘British’ empire, and also, if there was a good history of Briton, before the Anglo-Saxon barbarian invaders and the Norman feudal usurpers. And I thought that to answer that question, perhaps we need to look at the story (or myth) of King Arthur. But before discussing whether the story of King Arthur is a myth or is not a myth, we should first look at the idea of myths in general. Part 1 – On an Idea of MythsPlato’s Myth of the Shadows on the Wall of the Cave After listening to Cynthia Chung’s three wonderful classes on C.S. Lewis [part 1 – Out of the Silent Planet; part 2 – Perelandra; and especially part 3 – That Hideous Strength], her question of ‘myths’ got stuck on the back burner of my thinking cap. However, after some (early morning) fruitful discussions with some friends, a potential approach of looking at ‘myths’ came into view – that there are, perhaps, two different types of myths. At first, it reminded me of this difference that I have between Homer and Virgil. When reading the ‘Aeneid’ of Virgil, it seems to me that it’s all about a war among the gods, and that this is what determines the fate of Aeneas. But in Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, it seems that although the gods do influence the course of events, nonetheless Odysseus must determine or change his intention that will decide his fate. And I found this same difference when thinking about myths. Some myths excite our imagination with new and fabulous insights and emotions, while other myths excite our imagination with fantastic images and challenges, sometimes using omens and prophecies and mysteries. But not all myths are the same, as the better type of myths contain a hint of man’s moral sentiment. This moral sentiment can be like a compass, that leads us in the direction of the reason, or the purpose, or the ‘why’ of our intentions, and it nurtures our innocent imagination with a belief, or trust, or confidence in beauty, goodness and truth. For without this confidence in our moral compass, we are left with a different kind of intention of myths, that uses symbols and superstition, and magic and mysticism, in order to stimulate our senses with something that is simply strange or unusual or novel, that uses technique instead of art, and that aims at finding what is more powerful, not what is better. And this can leave us with an uneasy sense, or a lack of confidence, that there is any higher moral purpose. But then, I was listening to a wonderful presentation by Nick and Julia, ‘To Dance or not to Dance, that is the question’, and Nick was asked a question about confidence in ballet dancing (but when I think about it now, his answer is actually about life), and he said that the basis of confidence is ‘esteem’. And later, I got to thinking about this idea of esteem, and its relation to the idea of myths. If we thought that we would want to build up the cultural confidence of our population, then we would want to increase the ‘esteem’ of our population, both our own self-esteem but also our esteem for our fellow man. And then we could use a myth to portray our ‘hero’ or ‘heroine’ as someone that should be esteemed, because of his or her good character. And we would also use a tragic myth to portray those who we shouldn’t esteem, because of his or her bad character. And so, I think that in further trying to discover the uses of myths in our works of art, we should follow the advice of C.S. Lewis. In Lewis’s ‘Last Battle’ where it is said that Narnia was only a shadow or a copy of something in the real world, Lord Digory says, “It’s all in Plato, all in Plato: bless me, what do they teach them at these schools!” So now, we find ourselves treading on a path that was already explored by Plato – as to whether or not we should allow poets into our republic – where in book 7 of his ‘Republic’, Socrates presents us with his own myth – the fable of the shadows on the wall of the cave. [the following quotes are from Plato’s ‘Republic’, translation by C.D.C. Reeve]

Socrates then imagines a man who is freed, but because of the pain – from moving from his fetters and from looking at the light, he was puzzled and fled back to the shadows that he was able to see before; and he had to be dragged up into the light until he slowly got accustomed to seeing things in the light of the sun, and not as shadows.

Socrates then imagines that this man went back down into the cave, coming away from the light of the sun and going into the darkness of the cave, and he sat in his same seat as before.

Now, it seems that instead of having two types of myths, we have two types of myth-makers – one, like the highly-praised ‘perpetual prisoner’ who predicts the future by interpreting the shadows on the wall, and the other, like the ridiculed ‘escaped prisoner’ who returned to the cave trying to tell others about the world in the sunshine that he had seen. And while I don’t think that we should ban all myths, I also don’t think that we should ban all myth-makers, just as we should not ban all poets in our republic. Because it is up to us, to encourage those poets and those myth-makers whose intention was to act as a stepping stone to making us better persons, and to discourage those poets and myth-makers whose intention wasn’t to make us better persons, but were simply fantasies about ego or revenge or arrogance or narcissism. And with all that in mind, perhaps now we can look at which type of poet or myth-maker is telling us the story of King Arthur. Part 2 – the Malign and False History of Edward GibbonAccording to Xi Jinping, in order for a nation, a society, or a culture, to survive, it must progress in its science and technology, and especially in its arts. Because progress in its arts can give the members of that society, a confidence or a pride in its culture, that is called ‘cultural confidence’. [Note: By ‘cultural confidence’, I’m referring to an idea of Xi Jinping, that was posted in ‘the Blip Report for Sunday, March 19th 2023 – On China’s Cultural Confidence, by William Lyon Shoestrap’.] ‘Cultural confidence’ means having a ‘moral compass’ that can be used to measure an idea. But some people say that you can’t measure an idea. Well no, you can’t ‘physically’ measure the size or shape or weight of an idea, but you can measure its ‘directionality’ – whether an idea could be a good one, or whether it could be a bad one. And so having a ‘moral compass’ to measure the ‘directionality’ of an idea gives us a ‘cultural confidence’. But we, in the west, have been spoon-fed this utter nonsense called the ‘end of history’, that we don’t need to remember our past – just leave it, it’s not important, it’s irrelevant; that we don’t need to worry about the future – leave it to the technocrats and their AI robots to be taken care of; we only need to think about now – our ‘woke’, ‘trans-humanist’ now, and to go along with our ‘pre-determined’ future – with drugs and video games to keep us from getting too bored. President Xi points us to an opposite way of thinking: that we should cherish and learn from our past (of the good and the bad), and that we should wonder and dream about the good that our culture could do in our future, so in that way, we can have a ‘cultural confidence’ – a confidence or a pride in the positive contributions of our culture, that we can use to better live and work and contribute to the common good in the present. And it is our cultural confidence that is under attack today, by the North Atlantean managers of our cultural narrative. And in the same way that we should militarily defend our nation’s independence, we also should culturally defend our nation’s independence. And President Xi says that should be one of the missions for our artists, our musicians, our dancers, and our poets. And our historians too, I might add. Because it’s our story tellers that can help to strengthen our ‘cultural confidence’, and to try to regain that confidence, that we’ll need for our voyages into the future. And so, I thought it would be a good idea to go way back in our cultural history, and take a look at the story of King Arthur and who he really was, but also how that story had been changed and romanticized to weaken our cultural confidence. So first, let’s look at the interpretation of the story of King Arthur by the historian of the Roman Empire – Edward Gibbon. Between 1776 to 1789, Edward Gibbon’s ‘History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire’ was published – a massive six volume work of 71 chapters and almost 2500 pages – a very big book. And sometimes people write these huge books when the actual idea could have been said in a sentence or two, but they write these huge tomes to intimidate us into not questioning their accuracy and truth, as if to say that obviously this author must know what he’s talking about, since he wrote so much about it, but … maybe it’s all a facade – maybe it’s all much ado about nothing. In searching through those chapters, I found only one chapter, chapter 38, that contained all of 10 pages on the history of Briton after the Roman legions left, and that contained only 1 page – a mere 13 sentences on King Arthur. And that single page didn’t actually tell anything about historical events, but it was both a defamatory and a not very well researched historiography on Arthur. And it makes me think that this whole overly-hyped and overly-wordy book is of an equally shoddy workmanship. So, I’d advise you not to put this book on your ‘want-to-read’ list. Life is way too short. But anyway, I wanted to go through Gibbon’s attack on Arthur and try to point out his prejudices. [the following quotes are taken from chapter 38 of ‘The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire’ by Edward Gibbon]

The story of Arthur was not meant to ‘efface’ anyone, it was meant to provide us with an idea of a ‘hero’ – someone that we should try to be like, because of his good character, or because he accomplished something good. He was ‘illustrious’, yes, but he was not a god, he was but a hero. Gibbon does correctly say that Arthur was an ‘elective’ leader, indicating that people recognized something about him that made them ‘elect’ to follow his leadership.

What is the ‘most rational account’, Gibbon doesn’t say, so we’ll just have to take his word for it (he does have a lot of words). But ‘embittered by popular ingratitude and domestic misfortunes’ seems to contradict the earlier sentence that he was an ‘elective’ leader – meaning he had popular support. Why would the people turn against him? His ‘declining age’? But he only reigned a short time before he died. Perhaps it’s Gibbon that is embittered.

Gibbon is saying that the history of Arthur’s life is not very interesting, but the changes in how he is looked at, are more interesting. So, he is not studying the history of Arthur, but he is studying the subsequent perceptions of him.

Somehow even though Gibbon did not think Arthur’s history was ‘interesting’ enough to tell us about, he somehow did know that this history was ‘rudely embellished’ – no proof or discussion is allowed here to contradict his assertion. Besides, this history was told by some ‘obscure bards’ who were ‘odious’, and ‘unknown’, and (god-forbid) Welsh! Gibbon seems to be concerned with whether someone is considered acceptable and agreeable – not whether there is any truth in the story.

So, forget these losers from Wales, we have the Normans (who invaded Briton in 1066), who have ‘pride and curiosity’, and who were tempted with ‘fond credulity’ to listen to this story of Arthur, only because they both were against the Saxons. (i.e. the enemy of my enemy is my ally ?!?) However … had it not occurred to Gibbon (or maybe it had, but he wished to ignore it) that those ‘obscure bards’ revived this story of Arthur’s fight against the occupying Saxons to compare it with Briton’s fight at that time against the occupying Normans?

Gibbon now says that the story of Arthur is not history, but it’s merely a ‘romance’. But Geoffrey of Monmouth did not write a ‘romance’ of Arthur – he was trying to write a history of the kings of Briton, from the time of the first king, Brutus (the grandson of Aeneas of Troy), to the last king, Cadwaladr, before the Norman conquest. Geoffrey’s history was translated into Norman French – that Gibbon calls the ‘fashionable idiom of the times’, and it seems that the Normans ‘enriched with … incoherent ornaments’ that were the ‘fancy’ of that time. Gibbon seems to have a ‘fancy’ for the ‘fashionable’ Norman conquerors.

Gibbon is saying that the story of Arthur is just a tale that was added onto Virgil’s fable about Aeneas and the founding of Rome, and that it tried to ally Briton with the Roman Empire. But Geoffrey says that Arthur went to Gaul (France) to fight the Romans! Whose side is Gibbon really on – the Britons or the Romans?

Gibbon is claiming that Arthur’s battles were for imperial designs or for revenge, but Geoffrey says that Arthur freed these countries from the empire, and these countries then willingly joined with him in battle against the Roman emperor.

Gibbon is now using the Norman ‘romantic’ tales of Arthur to denigrate him, and to show that he was less ‘enterprising’ and less ‘valourous’ than the Normans.

Gibbon is implying that the knights of the crusades brought back stories of ‘Arabian magic’ that were then morphed into the Norman version of Merlin, and how this magic determined the ‘fate’ of Briton, not Arthur.

This Norman romance was studied and celebrated by everyone, says Gibbon, so that the ‘genuine heroes and historians of antiquity’ were disregarded. And so, he (inadvertently) shows how Briton might lose its cultural confidence.

And now, Gibbon claims, ‘the light of science and reason’ leads us ‘to question the existence of Arthur’. But Gibbon has not supplied us with any scientific or reasonable explanations for his arrival at this assertion – with only the dead weight of his stacked 2500 pages as his collateral. But why is Mr. Gibbon so pro-Roman and pro-Norman, and so anti-Briton and so anti-Arthur? To be honest, he should at least have stated his real intention. And so, it would seem that Mr. Gibbon is merely a highly-acclaimed interpreter of the shadows, for the amusement of the ‘perpetual prisoners’ in the cave. Perhaps, we should try to find an ‘escaped prisoner’ who could tell us the real story of King Arthur. Part 3 – Was there a King Arthur?Some historians claim that Arthur was an actual historical king, while others claim that he was a fictitious person. But without a doubt, all of these claims are, in some way, based on a book called the ‘History of the Kings of Britain’ written during the first half of the 11th century by a Welsh teacher and cleric, named Geoffrey of Monmouth. John Milton, a few years after writing ‘Paradise Lost’, wrote his own ‘History of Britain’, and in the middle of Book III, he suddenly stops and then spends the next four pages debating the existence of Arthur, since some ancient authors had said nothing of Arthur, except for one – Geoffrey of Monmouth. Milton writes:

As to how Geoffrey got a hold of this ‘fabulous’ story of the kings of Briton, he writes in his ‘Dedication’ of his ‘History of the Kings of Britain’, that first, he used traditional oral stories; and secondly, that he used a book that he was given by Walter, the archdeacon of Oxford, to translate into Latin from its original Briton: [quotes are from the ‘History of the Kings of Briton’, by Geoffrey of Monmouth, translated by Lewis Thorpe]

Most likely this ‘ancient book’ was the ‘Chronicles’ that was written by Saint Tysilio, a 7th century Welsh prince and abbot. It would seem to me that the ‘Chronicles’ started with Brutus – the first king of Briton, but ended with Cadwallader – the last Briton king, because Tysilio died about the same time as the end of the reign of Cadwallader in the 7th century. Geoffrey tells a wonderful story of Aeneas’s great-grandson, Brutus, who sailed to Briton (that was named after Brutus) and founded New Troy (now called London) –

Then he tells the story of the legendary kings of the Britons (including Lear and Cymbeline) that followed Brutus, until the Roman invasion and occupation, and after that, he tells of the invasion and occupation by the Saxons, up until the last king of Briton – Cadwallader. And during this period of the battles against the Saxons, Geoffrey tells the story of King Arthur, who unified the Britons against the many invaders, and against a return to being underlings of the dreaded Roman Empire!!! But Geoffrey’s story of Arthur should not be confused with the later invented and fabricated tales of Arthur, when during the age of the Crusades, this story of Arthur and his knights was changed, by people like Robert Wace and Chretien de Troyes, into a chivalric romance. Geoffrey wrote his ‘History’ around the year 1136 AD, during the reign of the Norman kings, who had invaded and occupied Britain under William of Normandy in 1066, and just before the start of the civil war among these Norman rulers of Briton, known as the ‘Anarchy’ – that would bring the Plantagenets to the throne of Briton. Geoffrey of Monmouth died around 1155, a few years before Henry II Plantagenet became the king of Briton; and Henry had also become king of the western half of France – with his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152. Eleanor had been married to King Louis VII Capet of France, but when their marriage was annulled, she was re-married to Henry II – less than 2 months after her marriage annulment to Louis VII!!! Eleanor would sponsor a Norman cleric, Robert Wace, and around 1155, at the time of the death of Geoffrey, Wace wrote his ‘Roman de Brut’, a romance of the ‘Chronicles’, that tries to imitate Geoffrey’s ‘History’, but that begins to bring in a ‘romantic’ version of Arthur and the Round Table. Wace later wrote a ‘Roman de Rou’, a romance about the history of the Norman kings, from the first Viking king Rollo, and of William the Conqueror and the ‘glorious’ Norman conquest of Briton. Eleanor’s daughter, Marie, became the sponsor of Chretien de Troyes, who a little later began to writing his romances of the round table, to further the Norman feudal take-over of Briton. Perhaps Geoffrey saw the coming civil war among the Normans, and so he told this story of the great King Arthur, so that one day perhaps the civil war and ‘Anarchy’ would end, and perhaps the Norman occupation would end, and maybe this story could be used to return the independence of Briton. But, why did Geoffrey write his ‘History’? For that, we can read the reason that he wrote in his ‘Dedication’ – that the deeds of these early kings – these kings from before the subjugation by the Roman Empire, until the kings before the subjugation by the Saxons, and their battles for independence from both – deserved to be told and to be praised ‘for all time’! Geoffrey writes:

Geoffrey translated Tysilio’s ‘Chronicles’ without ‘gaudy flowers of speech in other men’s gardens’, and did it in his own original straight-forward style, and he wrote it as a history story, and not as a chivalric romance story. Geoffrey was trying to write this s tory, as if he was an ‘escaped prisoner’, not as a ‘perpetual prisoner’ (like Gibbon). But before we read his story about King Arthur, perhaps first we should read his story about Merlin. Part 4 – The Story of MerlinOur story begins around the end of 4th century AD, when the Roman Empire was readying to withdraw their legions from Briton to go and fight elsewhere on the European continent, and all the men of military age were called to assemble at London, where they were addressed by Guithelinus, the Archbishop of London:

Some of these young men from Briton that Maximianus had earlier taken with him to Gaul, stayed in Gaul, and ended up settling on the peninsula of Brittany, that they called Armorica. But as soon as the Romans left, Briton was invaded and attacked by the Picts, along with the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. Guithelinus then crossed over to his fellow countrymen in Armorica to ask for their help. The king, Aldroenus, agreed to send his brother Constantine with soldiers under his command, and if he should free the country from the barbarians, then Guithelinus should place the crown on his head. When Constantine arrived in Briton, the young men joined him in battle and they were victorious, and all the Britons came together and made Constantine their king. [Constantine was Arthur’s grand-father.] But after Constantine was treasonously killed, the question was – who would succeed him? Constantine’s eldest son, Constans, had been raised in a monastic order, and his two younger sons, Ambrosius and Uther [Arthur’s father], ‘still lay in their cradles and could hardly be raised to the kingship’. Vortigern, a treasonous clan leader, convinced Constans that if he agreed to his plan, then Vortigern could make Constans king. Constans had been a monk – ‘what he had learned in the cloister had nothing with how to rule a kingdom’, and upon becoming king ‘he handed the entire government over to Vortigern’. Later, Constans was assassinated, and Vortigern usurped the throne. When the Picts, and the peoples of the neighboring islands revolted against Vortigern, Vortigern made a treaty with Hengist of the Saxons who had settled in Briton, who would assist him in his battles against the Picts, and Vortigern would give the Saxons grants of land. Also, Vortigern feared that either Ambrosius or Uther, who had fled to Brittany (in France) might sail from France to depose him, and so he allowed many more Saxons to come to Briton, to assist with his defence. Vortigern came to love the Saxons more than the Britons, and he even would marry the daughter of Hengist. But Vortigern would later be betrayed by Hengist and he was forced to flee to the western part of Briton. And here begins the story of Merlin.

The messengers found ‘Merlin’ – a boy who didn’t have a father. There is a little story about how his father was not a human, but was a daemon, from the spirit world, who had fallen in love with Merlin’s mother. Although later Hollywood romantics would try to say that Merlin was half demon and half human and that he was like an anti-Christ, NO, Merlin was half-daemon, like the daemon of Socrates – he was half-mortal and half-divine. And we will see the role of Merlin later. But now, when Merlin was presented to the king, he told him:

The magicians, who were terrified, said nothing.

This was done. A pool was duly found beneath the earth, and it was this which made the ground unsteady.

They remained silent, unable to utter a single sound.

After Vortigern ordered the pool to be drained, the two dragons emerged from the pool and breathed fire and fought bitterly. Vortigern ordered Merlin to explain what this battle meant.

Then Geoffrey adds another whole chapter (one that is not found in Tysilio’s ‘Chronicles’) concerning Merlin’s continuation of his interpretation of the two dragons:

Geoffrey continues with Merlin’s prophesy about the two dragons – a cryptic story of the history of Briton after King Arthur, until the last king Cadwallader. For this short period in Briton’s history between the Roman imperial rule and the Saxon conquest, Briton was again ruled independently by its own kings. So, here we see the emergence of Merlin into the story, in opposition to the superstitious and scheming magicians who were advising the king. Merlin was NOT a magician. Geoffrey calls him a soothsayer. Sooth is an old English word meaning truth. So a soothsayer is someone who tries to tell the truth, someone who tries to forecast or to predict the truth, or the future – a prognosticator, NOT a magician. Also at that time, Ambrosius and Uther sailed with an army from Armorica, landed in Briton, laid siege to the castle where Vortigern had sought safety, and burned it down, along with Vortigern. Then they marched to do battle against Hengist and the Saxons and defeated them. Hengist was executed but his son and the remaining Saxons begged for mercy, and Ambrosius, the new king, granted them the region near Scotland to live, and made a treaty with them. Now, at Salisbury, there were buried the leaders and princes of Briton who had been betrayed and murdered by Hengist and the Saxons, and so Ambrosius ‘collected carpenters and stone-masons together from every region and ordered them to use their skill to contrive some novel building which would stand forever in memory of such distinguished men. The whole band racked their brains and then confessed themselves beaten.’ Then Merlin was sent for, and when he arrived, Ambrosius ordered him to prophecy the future, because he wanted to hear some marvels from Merlin. But Merlin said:

There is much controversy about this mention of the ‘Giants’ and about the origin of the stone circles in Briton. The giants, as Geoffrey earlier said, were the inhabitants of Briton before the arrival of Brutus. But Geoffrey writes that at that time in Briton, they only seemed to think that the stones had medicinal properties, and they seemed to have forgotten about the astronomical uses and calendar dating uses for the stones. It’s like they’re coming out of a dark age. And I guess that 400 years suffering under the Roman Empire might not have helped any. Ambrosius sent his brother Uther [Arthur’s father] and 15,000 men, along with Merlin, to Ireland to remove the stones and bring them back to Briton. When they came to the stone ring, Merlin said:

‘They rigged up hawsers and ropes and they propped up scaling-ladders, each preparing what he thought most useful, but none of these things advanced an inch. When Merlin saw what a mess they were making he burst out laughing. He placed in position all the gear which he considered necessary and dismantled the stones more easily than you could ever believe. Once he had pulled them down, he had them carried to the ships and stored on board, and they set sail once more for Briton with joy in their hearts.’ Back in Briton, Merlin had the stones placed in a circle around the sepulchre, in exactly the same way as they had been arranged on Mount Killaraus in Ireland. Merlin, Uther and the men did not use magic, or brute strength to move the stones and to reconstruct them, they used ‘skill’. Ambrosius would be poisoned by a treacherous Saxon, and Uther [Arthur’s father] would become king. And now we are ready to read the story of King Arthur. Part 5 – The Story of ArthurAmbrosius would be poisoned by a treacherous Saxon, and Uther [Arthur’s father] would become king. Years later, when Uther died, the Saxons called over more of their countrymen from Germany to over-run and to kill the Britons. The provincial leaders of Briton assembled and asked Dubricius, the archbishop of the City of the Legions [Caerleon], to place the crown of Briton on the young Arthur.

Arthur wished to battle the Saxon invaders, who had usurped his ‘rightful inheritance’ to the kingship of Briton. The Saxon leaders assembled a vast army of Saxons, Scots, and Picts, whiled six hundred ships with more men arrived from Saxony. Arthur sent messengers to his cousin Hoel in Armorica (Brittany) in France, who then sent 15,000 troops to help Arthur. Arthur and Hoel then marched to meet the Saxon army and defeated them. The Saxons promised to leave all their gold and silver, if Arthur permitted them to return to Saxony. Arthur permitted them to leave but to take with them nothing but their boats. Once the Saxons had sailed, they reneged on their promise and turned back to Briton and began to lay waste to the countryside. Arthur marched south to meet the Saxons at Bath, and told his men:

Geoffrey was portraying Arthur as one of the first Christian kings of Briton. After the Diocletian persecution of the Christians in 393, and after the final Roman army withdrawal around 401, the invasions of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes destroyed most of what was left of the Christian churches in eastern Briton. But the Christian churches survived in the unconquered western part of the island. And I think this was to say that now that the Roman legions had left Briton, they didn’t have to keep that Roman Empire culture anymore, that they shouldn’t just go back to a pagan culture, as represented by the Saxons, but something better should be tried. Now, Christianity was a new religion at that time, and like Judaism, had been trying to survive under the Roman Empire. While the Britons were converting to Christianity, the prophet Mohammad wouldn’t be born for another 100 years, and the Khazars wouldn’t convert to Judaism for another 200 years or so. During the battle, the Saxon leaders and thousands of others were killed, and the remaining troops fled towards their ships. But Arthur sent Cador, the duke of Cornwall, after the fleeing Saxons, and Cador seized their ships first, and then cut the Saxons to pieces. Arthur marched north to confront the Scots and the Picts, and besieged them at Loch Lomond. [I’m not sure if Arthur took the high-road or if he took the low-road to get to Loch Lomond, but it should be something to muse upon.] Meanwhile, Gilmaurius, king of Ireland, arrived with ‘a horde of pagans’ to help the besieged Scots. Arthur raised the siege of the Scots, and marched to meet the Irish, defeated them ‘mercilessly’ and forced them to return home to Ireland. Arthur now turned back against the Scots and Picts ‘with unparalleled severity’. When the bishops of Scotland begged pity of Arthur, Arthur was moved to tears and granted a pardon to their people. Arthur then went to York where he met three brothers who had been princes before the Saxon invasion, and he gave them the kingships of Scotland – Albany, Moray, and Lothian. The next summer, Arthur sailed to Ireland and again defeated the horde of Gilmaurius, and all the princes of that country surrendered. Arthur then sailed to Iceland and subdued the island. Upon hearing this, the kings of Gotland and Orkneys came and promised tribute to Arthur. Arthur returned to Briton, and he established the whole of his kingdom in a state of lasting peace and then remained there for the next twelve years. Arthur later sailed to Gaul, that was under the Roman Tribune Frollo, who ruled in the name of Emperor Leo. After failing to defeat Arthur, Frollo quit the field and fled to Paris. After a month of siege, in order to stop the people from dying of hunger, Arthur agreed to Frollo’s request to meet in single combat – “whoever was victorious should take the kingdom of the other”. When Arthur had defeated Frollo, Arthur subdued the remaining provinces of Gaul. Then Arthur returned to Paris, and called an assembly of the clergy and the people, and settled the government of the realm peacefully and legally. With Gaul now pacified, Arthur returned to Briton, and held a plenary court ‘to renew the closest possible pacts of peace with his chieftains’, at Caerleon, the City of the Legions, a city that was adorned with royal palaces and with two famous churches – to the martyrs Julius and Aaron, and also a college, where Arthur used astronomers, not magicians, to forecast the future.

And here we see the importance of Merlin – how did Briton change from the magicians of Vortigern to the astronomers of Arthur? Through Merlin – the stepping stone from magic to science. Merlin was not a return to the ‘alleged’ druid magicians, but a return to ancient Celtic astronomers – before their destruction under the Roman Empire! That’s the real Merlin – not the romantic evil wizard of a Hollywood romance, but as a stepping stone out of the mysticism of the Roman magicians. Now, invited to this meeting, were all the kings of Briton and Scotland, and all the leaders of the provinces of Briton, and all the kings of the ‘Islands’ – Ireland, Iceland, Gotland, Orkneys, Norway and Denmark, and the leaders of the provinces of Gaul – “… there remained no prince of any distinction this side of Spain who did not come when he received his invitation. There was nothing remarkable in this: for Arthur’s generosity was known throughout the whole world and this made all men love him.” But most interesting in this assembly, were the leaders of the church in Briton – the archbishops of the three metropolitan sees: London and York, and ‘Dubricius from the City of the Legion … who was the Primate of Briton and legate of the Papal See …’

Geoffrey is talking about David – who became Saint David, the patron saint of Wales – who is Arthur’s uncle!!! [although sometimes, the translation from the manuscripts have ‘uncle’ for ‘nephew’ or ‘cousin’, and so maybe David was Arthur’s cousin.] And it was then that Arthur received twelve envoys with this letter from Lucius Hiberius, the Procurator of the Roman Empire, who was outraged at Arthur:

This letter was read aloud to Arthur and to all the assembled kings and other leaders, who then met to consider what to do. Arthur told them that when these lands were snatched from the Empire, the Empire made no effort to defend them, but now the Empire was demanding tribute!

One after the other, the kings of Briton and Scotland and the Islands, and the leaders of the neighbouring provinces of Gaul, all pledged their troops and to enter his service. And Arthur left his nephew Mordred and his Queen Guinevere in charge of defending Briton, and sailed with his army to Gaul – to meet the Emperor’s army. Much is told by Geoffrey of the story of their meeting, of the different strategies and of the battles that followed – this seems to be the most important part of the story of Arthur – and of Arthur addressing his troops before the battle at the valley of Saussy:

Arthur is saying that after he defeated the Saxon invaders of Briton, he then delivered these peoples from the Roman Empire! And now he was defending that newly-won freedom from the Empire! In the end, after ferocious fighting, the Britons won the day, and Lucius was killed – pierced through by an unknown hand. Arthur had his body sent back to the Senate in Rome, with the message that there would be no tribute from Briton. Arthur’s plan had been that once the Roman army was defeated in the field, then Arthur would set off for Rome. What if Arthur had been able to march to Rome, and freed Rome from the Empire? But while he was making his way across the mountains into Italy, word came that his nephew Mordred, who Arthur had left in charge of Briton, had put the crown on his own head, and was ruling with Queen Guinevere! Arthur now had to turn back from his march on to Rome and he sent Hoel to restore peace among the Gauls, and then he made his way home to Briton. Mordred had made an agreement with Chelric, the Saxon leader, to bring 800 hundred ships to join him, in return for which he would receive much of the island to rule. Mordred also brough the Scots and Picts and Irish into his alliance, and he marched with his army to meet Arthur when he landed. After a third brutal and bloody battle, Mordred’s army was defeated, and both Mordred and Chelric were killed.

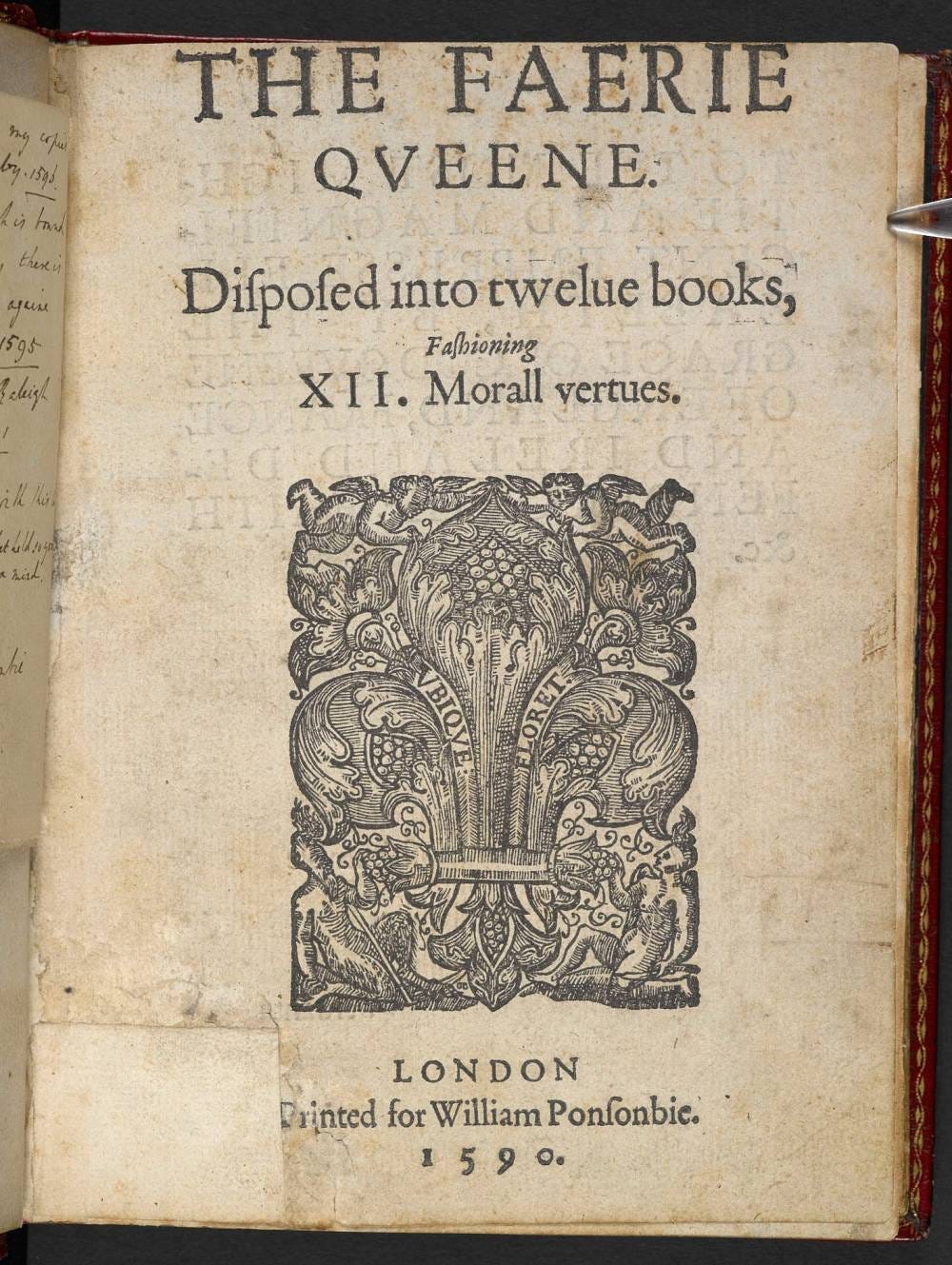

There is much controversy regarding the location of the Isle of Avalon, and regarding the year of Arthur’s death, and whether Arthur actually died, and if he will someday return. But I think that Geoffrey showed that Arthur was the hero of the independence of Briton – both from the Saxon invaders and from the Roman Empire; and that Geoffrey’s idea of Arthur’s return is not a physical return, but a return of the spirit of Arthur, and a return of the people of Briton to their independence – including from today’s modern variant of the Roman/Saxon/Norman usurpers – the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, i.e. the House of Windsor. Part 6 – The Land of the Faerie QueeneSo, in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s history story of Briton’s hero, King Arthur, there are no lovey-dovey affairs of Guinevere, there are no carpet knights sitting around the round table (or chasing after windmills), and there is no absurd search for the holy grail. Because we were not on a quest for the holy grail, but on a quest for beauty, goodness and truth. All these romantic chivalric myths were added later to try to mystify the true story of Arthur, and for a different purpose than the intention of Geoffrey – that the deeds of these men should be remembered for all time. And Arthur should be remembered, by Geoffrey’s story and not by the Norman romantic fantasies. Or the recent Hollywood versions either. But, there’s another way in which Arthur is remembered – in a different way than what one might have imagined. About 250 years after Geoffrey of Monmouth, we see another Geoffrey – Geoffrey Chaucer, who wrote the Canterbury Tales, and in all of his poems and in all of his tales, he only mentions King Arthur once – in the wife of bath’s tale, and only in the first few paragraphs:

It would seem that not only did Arthur free Briton from the Roman Empire and from the magicians, but he also freed the artists, and the musicians, and the dancers, and the poets. And the land of Briton became a land of mirth and fables, and full with elves and faeries. But when we lose our independence, do we also lose our ability to see this land of faerie? Because now, no one sees elves anymore (maybe Robert Frost was the last one) – we’ve become literalists and scholastics and nominalists and empiricists – we cannot see the land of faerie anymore, we only are shown the land of escapism, a land that claims to be neither good nor bad (as if such a thing were possible) and it’s not like the escape of a prisoner, but it’s more like the escape of a deserter. But then, as some story-tellers have said, maybe it was because the fairies and elves spoke to us in the language of old Briton, of old Celtic, and old Welsh, a language that we didn’t understand anymore. And so, they said, the fairies and elves took up this mish-mash of Norman and Saxon utterings and grunts, and they turned it into something they called Anglish – something that we could use to talk to them again. Perhaps. For it seems that 200 years after Chaucer, we see this land reappear in Edmund Spenser’s ‘Faerie Queen’, as Prince Arthur searches for the Queen of Fairyland. The 1590 publication of the first three books of the ‘Faerie Queene’ began with “A Letter of the Author’s” – a letter written by Spenser to Sir Walter Raleigh – ‘expounding his whole intention in the course of this work’.

According to Spenser, in order to discover beauty, we must be like a Prince Arthur – striving to be a person of virtuous and gentle discipline, to become like a King Arthur, who, in real life, defended Briton from the barbarian invasion of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, and also from a re-conquest by the Roman Empire, and in doing so, allowed for the subsequent spread of an esteem for an independent cultural confidence. And I think that just as Arthur was a stepping stone that leads from the Roman Empire’s enslavement towards Briton’s independence, and just as Merlin was a stepping stone that leads from the magicians to the astronomers, then perhaps the elves and fairies could be seen as a sign that between the worlds of fact and fiction, there are stepping stones that lead us to a whole other world – a world of ideas, a world of intentions … and a world of inventions. Our stories, like our language, didn’t evolve, but were invented (!!!) to help us explore this world of ideas. And likewise, we didn’t evolve like one of Darwin’s apes, but we were invented, by ideas. But these stories of the world of ideas should be used to better help us to see in the real world, and not to simply create chaos, that can only be fixed by the magicians. Maybe we don’t need the magic of the magicians or the power of the empire, of the Leviathan, to impose order over the chaos. Maybe the world isn’t in chaos after all, but is merely inter-twined and inter-connected mysteries that our story-tellers help us to unravel. But where this idea of elves and faeries, and of that mythical land ‘full with faeries’, originally came from, I’m not sure. But we see this land once more in Shakespeare’s (i.e. Christopher Marlowe’s) ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’ where we find the King and Queen of Fairyland; and we can catch a glimpse of ‘Queen Mab’ in Shakespeare / Marlowe’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’, and of the ‘Faery Mab’ in John Milton’s poem ‘L’Allegro’ and again in Percy Shelley’s poem ‘Queen Mab’. It’s been said that John Milton had once thought of writing an epic about King Arthur, but perhaps, after writing his tracts to justify the execution of the king, and after writing his tracts in support of establishing an English commonwealth, he may have decided against writing an epic about a king, even if it was of good King Arthur. So, instead he wrote his epic ‘Paradise Lost’ about devils and angels, and Adam and Eve and a garden of Eden, that seems to have been taken from a fabulous story by Moses, and that, like Geoffrey, perhaps, was embellished by his own wonderful imagination. And J.R.R. (Ronald) Tolkien was writing a half-finished story about King Arthur that he put aside, to begin writing a story about elves and dwarves, and a curious hobbit named Bilbo. Perhaps as well as stories of our heroes like Arthur, stories of our elves and faeries were also left as a gift to us, a ‘promethean’ gift to man – the gift of story-telling. Since, while we sat around that gift of fire on a quiet, dark night, we discovered something to do – story-telling. Perhaps, but that is a whole other story to explore, another time. And so now, in conclusion, we should say that: If Geoffrey’s ‘History’ is historically accurate, then we owe Geoffrey a world of gratitude – for having collected oral traditions and translated ancient written tracts and assembled them into a real history of King Arthur. But if Geoffrey’s ‘History’ has simply taken certain historical events and then embellished them with his own imaginary tale, then we still owe Geoffrey a world of gratitude – for giving birth to this fabulous story of King Arthur. I’ll leave it up to you to decide for yourself, which of these two conclusions you believe. But for me, I like to believe in both. And perhaps, some day in our future, when people say Britain, we won’t think of the British Empire anymore, but we’ll think of King Arthur and of the independence of Briton from the empire. And perhaps we’ll think of the elves and fairies again too. And perhaps, as Mark Twain might have thought – ‘reports of their death were grossly exaggerated’! The author recently delivered a comprehensive lecture on this topic which can be watched here:  The Rising Tide Foundation is a non-profit organization based in Montreal, Canada, focused on facilitating greater bridges between east and west while also providing a service that includes geopolitical analysis, research in the arts, philosophy, sciences and history. Consider supporting our work by subscribing to our substack page and Telegram channel at t.me/RisingTideFoundation. Also watch for free our RTF Docu-Series “Escaping Calypso’s Island: A Journey Out of Our Green Delusion.” You're currently a free subscriber to Rising Tide Foundation. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Saturday, February 17, 2024

In Defence of King Arthur

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Invitation (for paid subscribers) Assassinations Sans Frontiere: Four murder plots that triggered WW1 (featuring M…

The world is once again sitting on the precipice of a slide into multi-generational terror, depopulation and war. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Greetings everyone ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Rising Tide Foundation cross-posted a post from Matt Ehret's Insights Rising Tide Foundation Sep 25 · Rising Tide Foundation Come see M...

-

March 16 at 2pm Eastern Time ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

No comments:

Post a Comment