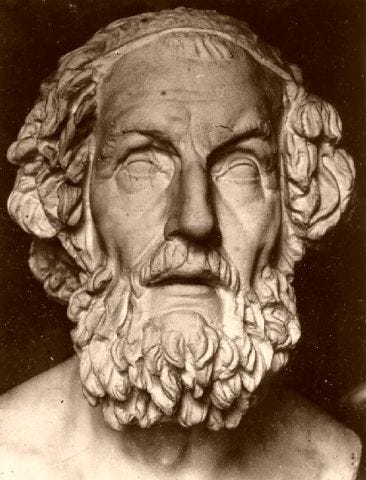

By Cynthia ChungToday, perhaps more so than at any time in history, we are experiencing a divide between what is considered to be the “domain” or “confinement” of art as wholly separate from the domain of “politics.” The irony of such a perception is its failure to recognise that the root of our political system was enjoined with the arts from its very inception. Looking at ancient Egypt and Athens, mythos was dominant in all spheres of thought. Mythos, which pertains to anything transmitted by word of mouth, i.e. fables, legends, narratives, tales etc., would often hold within it a significant truth or meaning for the society as a whole. In other words, ideas that were pervasive in these cultures and shaped all aspects of life including its politics and sciences were shaped by mythoi, or the art of story-telling. Homer’s great poems that are left to us today, The Iliad and The Odyssey, describe the events of the Trojan War and its immediate aftermath, events which marked the descent of Greece into a dark age. Following the Trojan War, approx. 1190 BCE, the civilization of mainland Greece collapsed, written language was lost, cities disappeared. The Iliad and The Odyssey, written around 700 BCE heralded the reversal of the collapse, and the beginnings of Classical Greek culture. These epic stories of Homer which had been passed down through the centuries by poet bards who had memorised entire texts, would travel all throughout Greece and recount these tales. These “stories” became a dominant cultural reference point for all of Greece and beyond, and are greatly influential to this day. Why do you think that is? Is it purely the fancy of the imagination? Or can our mind, situated in the realm of the imagination, come to a profound discovery through mere “story-telling”? As Shelley wrote in his “A Defense of Poetry”:

Aeschylus (523-456 BCE), Sophocles (497-406 BCE) and Euripides (480-406 BCE) are considered to be the three greatest Greek tragedians. Greek tragedy competitions would be held between three different playwrights (selected half a year before), who were required to compose three tragedies and one satyr play each. The Greek tragedy festivities were second only to the Athletic competitions. The Greek tragedies were not just for entertainment but often would contain a warning for those who did not heed the ill-fated decisions of its characters. Often, epic stories from the distant past would be selected due to their relevance to a present day situation or conflict. Much like during the time of Shakespeare, one could not simply criticize a war or a conduct of a specific ruling or influential group, but rather the dramatist would pick characters from either a fictional world or a distant past to showcase a foretelling. To reveal a truth that has remained hidden. One could argue, those were simpler times, in today’s calculating and information-dominated world we cannot afford such fanciful, inexact thinking within the realm of “politics”. Well I would argue that this in fact only increases the urgency of art’s reintroduction into the realm of “reality” so to speak. For example, have you ever searched for something, stubbornly staring at a specific area you were certain you left the item, but it is not there. You then proceed to rummage through your entire house, and then upon returning to that same spot, you realise, that the item you were looking for was always there? It was in fact right in front of you, but for some inexplicable reason, you could not “see” it at the time. Well, in short, poetry gives us that ability to “see” something that has remained hidden from us. It is not simply a matter of “logic” or “reason” that we can compel such things to reveal themselves to us, and no matter how much effort we put into insisting with our senses that we know something to be true, even our very eyes have the ability to show us a false image. In order to investigate this further, let us take a look at Shelley’s constitution for poets and statesmen alike, “A Defence of Poetry.” As Shelley discussed in this essay, there are:

As Shelley defines it, poetry may be defined as “the expression of the imagination.”

What Shelley is discussing here is the relevance of imagination as not something fanciful but in fact something that is crucial if a society is to advance and prosper. This is not an arbitrary form of imagination but rather the ability to see a potential, something that has yet to take shape; something that we can never hold and dissect, such as the concept of justice, or the concept of love, something that partakes in the eternal. Shelley further says:

Shelley here, is very clearly using the lessons of Plato, that every individual’s actions and thoughts in life are to seek for and acquire pleasure. However, there are two forms of pleasure, one that partakes in the eternal and one that partakes in the temporal. The latter can be said to be the domain of narrow utility. [For a more in depth study of this refer to Plato’s Gorgias.] The most basic utility is a necessary condition for sustaining life. Our bodies after all, are made of flesh, and we require a constant replenishing of temporal goods, such as air, food, water, warmth. We take pleasure in these and that is a fine thing. However, there is a problem that arises if we claim that that is the end all, be all of our existence. Our mind, though some will argue this point, is not fully participating in the temporal realm, but rather it is also situated in the eternal. The fact that we can even fathom a concept of the eternal is evidence towards this. Our minds have the ability to partake in something that is beyond our direct sensing of a physical space time, and thus it partakes in the eternal. Let us read on:

Shelley is warning, that to blindly follow the “calculating faculty” and straight-forward “utility” of a mere physical object will rob us of what it is to be human. These are indeed necessary “tools” but they should never be used to “govern” an individual or a people. Therefore, how do we resolve this? How do we create and maintain a society that is fluid enough to increasingly move towards improvement in all its spheres? It must have at its core “the soul” so to speak of what it is to be human and how this relates to something entirely larger than ourselves and our lifetime. Shelley states:

Here Shelley is making the point that the truly useful, the truly pleasurable, is what makes us truly good, truly our most “human.” However, this “highest sense” of pleasure is often linked with pain. This tends to deal with the struggle between the mortal v.s. immortal qualities of our being. [For a more in depth study of this refer to Schiller’s “On Tragic Art.”] For instance, our mortality, in of itself, is a tragic thing. That our time on this earth is only for a relatively short while partakes in a type of pain, yet when our appreciation for life is all the more cherished and sacred, it gives us a greater, more rich and colourful pleasure than if we took such a life for granted. However, there is an even higher sharing of pleasure and pain and this partakes in the eternal. That is, why as an audience are we moved by the sacrifice of a character on stage for some other good? Why are we moved by such stories as Joan of Arc, Braveheart, and Romeo and Juliet? It is in fact the most contrary thing to “logic” or “reason,” to go against our very physical existence, is it not? To forfeit life for a “cause”, for an “idea”? None of us desire death, so why would we be moved by another’s sacrifice of life for something beyond our physical existence? It is a reflection that our truest and deepest desire is not for prolonging a mortal life, but rather the longing to participate to the greatest degree in something immortal. Let us return to Shelley:

The best way to understand what Shelley is referring to here, is that narrow utility and dogmatic custom/tradition are closer to being truly dead, than the sacrifice of a Joan of Arc. To merely prolong a physical existence in all our bodily functions is no different from the existence of someone who has been lobotomised or is in a comatose state. The greatest value to life is what partakes in something beyond merely the physical. “The mind is its own place, and of itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven,” means that our mind is what shapes our “reality,” it is what shapes our choices, our decisions, our future…our possibilities. Depending on the decisions we make, the course of our lives and of entire civilizations can be changed for the better or worse. Imagination allows a hopeless situation to become a fortuitous one. It is imagination that seizes a rare opportunity when it presents itself, and it is truly from the imagination that we are able to “seize the day,” as the story of Dumas’ “The Count of Monte Cristo” beautifully exemplifies to us. And thus we conclude with:

For information on our upcoming symposium “Towards an Age of Creative Reason: Why the Poetic Principle is Imperative to Statecraft” click here.The Rising Tide Foundation is a non-profit organization based in Montreal, Canada, focused on facilitating greater bridges between east and west while also providing a service that includes geopolitical analysis, research in the arts, philosophy, sciences and history. Consider supporting our work by subscribing to our substack page and Telegram channel at t.me/RisingTideFoundation.

|

Saturday, December 9, 2023

Why the Poetic Principle is Imperative for Statecraft

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Respect Is Earned Through Patterns, Not Moments

One Impressive Act Will Never Replace Consistency ...

-

Greetings everyone ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Rising Tide Foundation cross-posted a post from Matt Ehret's Insights Rising Tide Foundation Sep 25 · Rising Tide Foundation Come see M...

-

March 16 at 2pm Eastern Time ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

No comments:

Post a Comment