In 1996, a nest of American-born imperialists revolving around Paul Wolfowitz, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and Richard Perle created a new think tank called “The Project for a New American Century.” While the principled aim of the think tank ultimately hinged on a new “Pearl Harbor moment” that would justify a new era of regime-change wars in the Middle East, a secondary but equally important part of the formula involved the dominance of “Greater Israel” Likud fanatics then taking power over the murdered body of Yitzhak Rabin. It was toward the start of the new regime of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that Richard Perle wrote the report “Clean Break: A Strategy for Securing the Realm,” which outlined a series of goals that would govern the strategic vision of Washington and Tel Aviv for the next two decades. It called for:

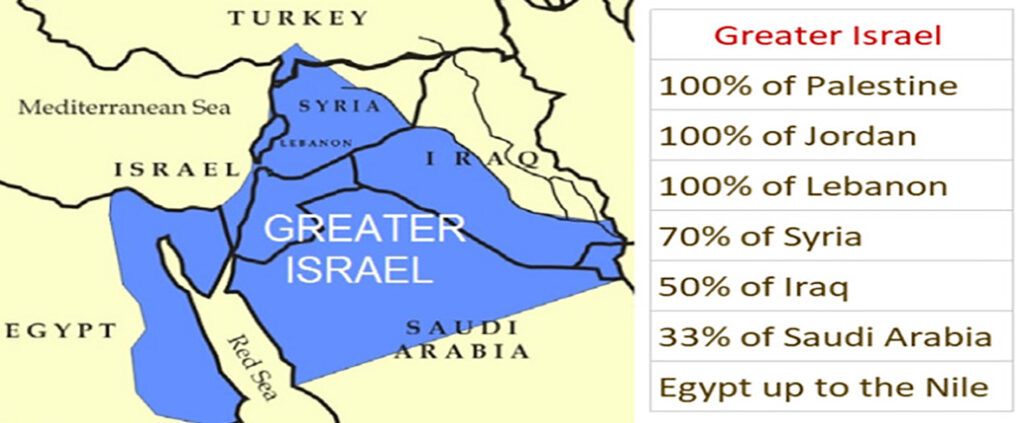

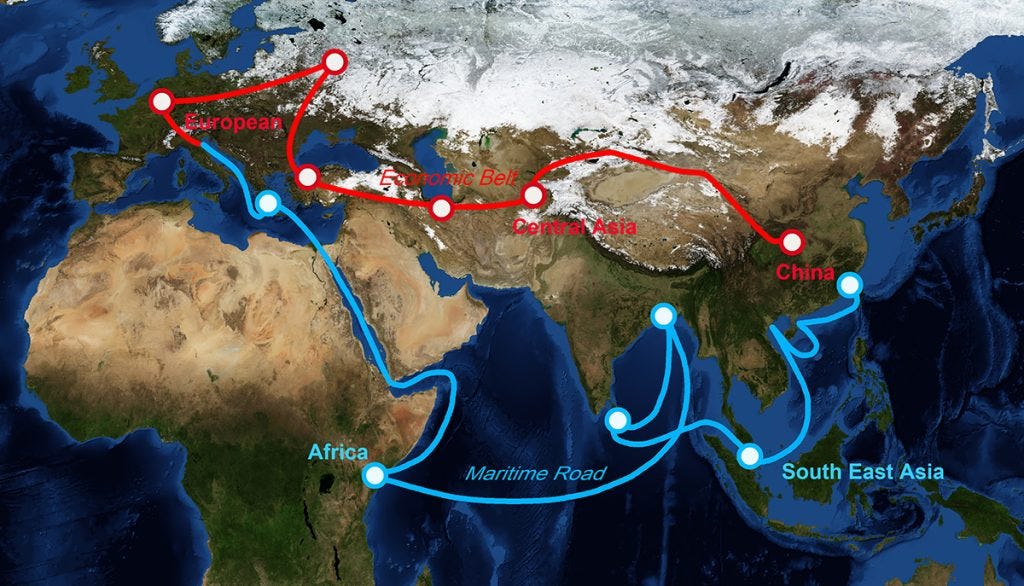

In 2007, General Wesley Clark added even more detail to this neocon program when he revealed the content of a discussion he had with Wolfowitz and Rumsfeld 10 days after 9/11. General Clark stated that he was told of planned invasions of seven countries scheduled to take place within five years… namely: “Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Iran.”  This program was, in short, a recipe for establishing the long-awaited “Greater Israel” promoted by the likes of Theodor Herzl, Vladimir Jabotinsky, and Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook over a century ago. While the Anglo-Zionist timeline was disrupted over the ensuing years (sometimes involving brave intervention by individuals within America’s intelligence community), the intention embedded in “Clean Break” never disappeared. With the coming breakdown of the over-inflated Western financial system on one side and the emergence of a viable new multipolar security and economic architecture on the other side, it appears the ghouls that orchestrated 9/11, assassinated Rabin (1995) and Arafat (2004), and revived the Crusades have decided to kick over the chess board. Conducting a rational analysis of the motives for this type of dynamic poses a major difficulty for any geopolitical commentator used to thinking in academically acceptable terms, which presume that rational self-interest animates the players within a game. In this case, rational self-interest is infected by heavy doses of self-delusional Hegemonism, fanatical imperial zealotry, and end-times eschatology with a Messianic twist (taking both Christian and Jewish forms). Sifting out Order from ChaosNetanyahu and his supporters in America and Britain appear to be supportive of Israel’s ambition to provoke a vast regional war, on the one hand, while also believing that perhaps they will be able to use Israel as a wedge to disrupt Russian and Chinese-led development corridors (BRI, short for Belt and Road Initiative, and International North–South Transport Corridor), on the other hand. These Eurasian development corridors are rightfully seen as an existential threat to Western imperialists as they provide the foundation for the viability of a new economic architecture based on long-term thinking and mutual cooperation. The role Israel is expected to play in an anti-BRI agenda is meant to take the form of two major projects within this ivory tower fantasy game of imperial Rand-style scenario builders. These are:

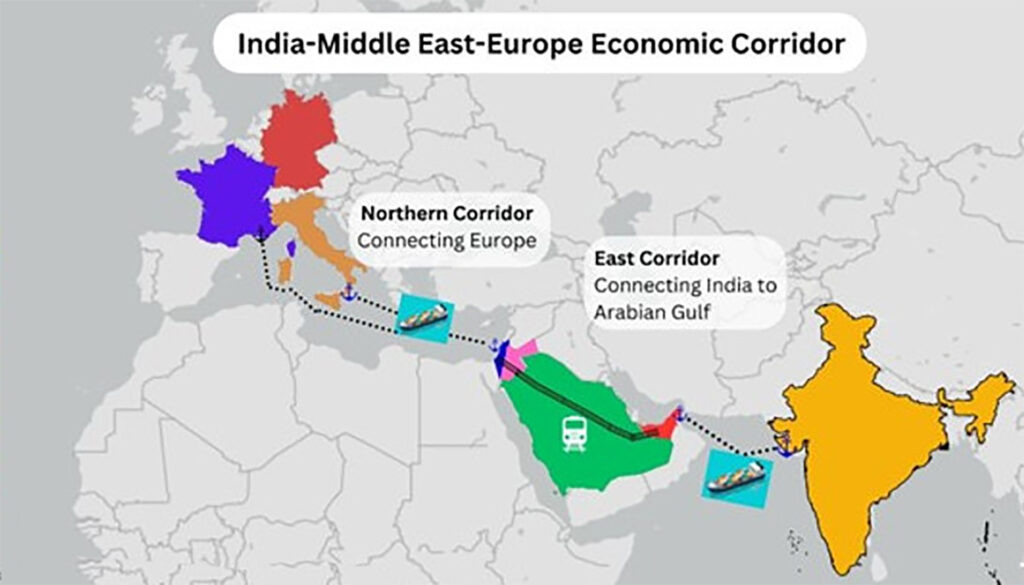

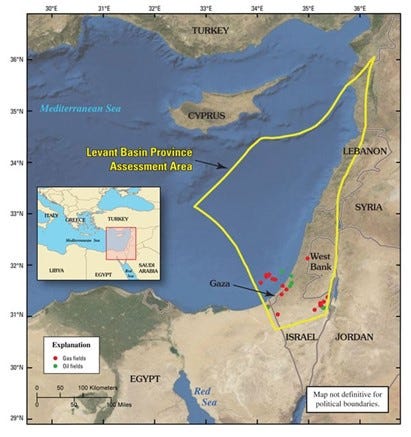

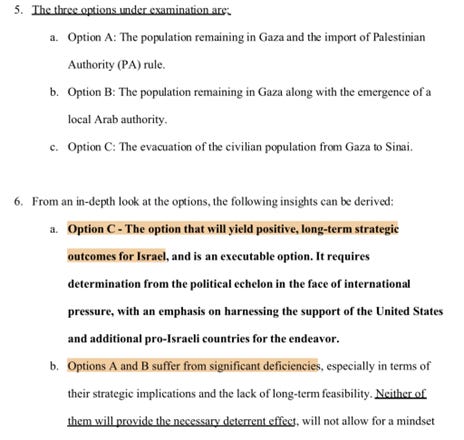

The IMEEC FantasyThe India Middle East Europe Economic Corridor appeared to be a non-starter since it was first announced over two years ago. However, with the potential radical destabilization of the broader Middle East that may emerge out of a war on Iran, it is possible that this project has been given a new life and may represent a dangerous alternative to the Chinese-led Belt and Road Initiative. Is Narendra Modi more committed to Eurasian prosperity, or is he being pulled into this dangerous alliance? While India plays a strategically important role as a leading member of the BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and a vital ally of Russia, the western–IMEEC pull is as dangerous as it is real. With Modi’s recent two-day state visit to Israel as a guest of honor from February 25 to 27, the Indian leader re-asserted his belief in the importance of the IMEEC, as well as the I2U2, stating: “We will also work closely in different formats, such as the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor and the I2U2 frameworks between India, Israel, UAE and the US.” he I2U2 was first announced in 2022 and has been compared to Middle East QUAD that would counter the influence of Iran and would parallel a similar power block forming in the Pacific under a US–India–Japan–Australian alliance to counter China. During his talks with Netanyahu, Modi re-asserted his support for the Abraham Accords and gave his full support to Israel in opposition to Palestinian terrorists, stating: “Like you, we have a consistent and uncompromising policy of zero tolerance for terrorism with no double standards” and that “India stands with Israel, firmly, with full conviction, in this moment, and beyond.” During the meeting, Netanyahu emphasized his plan for a Hexagon Alliance encompassing Greece, Cyprus, India, Israel and an unspecified number of Arab and African states friendly to Israel. On top of agreements for Artificial Intelligence, business exchange, critical minerals, energy, and defense, a much more comprehensive India–Israel Free Trade Deal and Strategic Partnership was also discussed. A Real Concern: Gaza Offshore Energy StealIf developed, it is believed that these offshore resources would transform Israel into a global energy hub supporting the glory of Greater Israel as a new empire. This vast deposit off the coast of Gaza (and thus under the legal ownership of the people of Gaza) was first discovered in 1999 when a company called British Gas discovered deposits of approximately one trillion cubic feet of natural gas 19 miles off the Gaza coast. Agreements to develop this project at a cost of $1.2 billion soon followed. Although Yassir Arafat expressed an active interest in developing these resources two decades ago, Israel worked tirelessly to block the Palestinian Investment Fund (the fund responsible for carrying out the development) from extending investments into the project, using the argument that “funding may be used to support terrorism.” When Hamas was elected in 2007, Israel’s efforts to block funding for the Gaza marine field vastly increased. This is perhaps why Hamas’ 2007 victory was celebrated by none other than Israeli intelligence Chief Amos Yadlin, who cabled US Ambassador Richard Jones that he would be “happy” if Hamas formed a government because “the IDF could then deal with Gaza as a hostile state.” In the cable made available by Wikileaks, Yadlin also dismissed concerns about Iranian influence within a Hamas government “as long as they [Hamas-controlled Gaza] don’t have a port.” Yadlin’s comments were echoed in 2019 by Netanyahu himself, who said to Likud Knesset members: “Anyone who wants to thwart the establishment of a Palestinian state has to support bolstering Hamas and transferring money to Hamas … This is part of our strategy — to isolate the Palestinians in Gaza from the Palestinians in the West Bank.” [emphasis added] When a consortium of Israeli, American, and Australian energy companies discovered even more oil and natural gas deposits in the Levant Basin “off the coast of Israel” in 2010–2011, the western Mediterranean became a potential global gamechanger in oil geopolitics with the US Department of the Interior 2010 report estimating “1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil and a mean of 122 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas in the Levantine basin.” Experts estimate that these deposits carry at least $453 billion in value. Former Israeli Energy Minister Karine Elharrar described Israel’s ambition to become a global energy hub after signing a 2022 memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Egypt promising to develop the gas fields: “This is a historical moment in which the small country of Israel becomes a significant player in the global energy market. The MOU will enable Israel, for the first time, to export Israeli natural gas to Europe, and it is even more impressive looking at the significant set of agreements we signed over the last year, which position Israel, and Israeli energy and water sectors as a key global player.” Elharrar’s words carried a bitter aftertaste as it had already been proven that Israel intentionally blocked the development of these offshore fields for two decades — to the detriment of millions of Palestinian lives (and ironically Israel’s own economy). This fact was outlined in great detail by a 2019 report by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which stated: “Geologists and natural resources economists have confirmed that the Occupied Palestinian Territory lies above sizeable reservoirs of oil and natural gas wealth, in Area C of the occupied West Bank and the Mediterranean coast off the Gaza Strip. However, occupation continues to prevent Palestinians from developing their energy fields so as to exploit and benefit from such assets. As such, the Palestinian people have been denied the benefits of using this natural resource to finance socioeconomic development and meet their need for energy. The accumulated losses are estimated in the billions of dollars. The longer Israel prevents Palestinians from exploiting their own oil and natural gas reserves, the greater the opportunity costs and the greater the total costs of the occupation borne by Palestinians become. This study identifies and assesses existing and potential Palestinian oil and natural gas reserves that could be exploited for the benefit of the Palestinian people, which Israel is either preventing them from exploiting or is exploiting without due regard for international law.” If Israel wishes to have full control over Gaza’s maritime oil/gas reserves, it can only achieve its goal if the legal owners and beneficiaries living in Gaza disappear. On October 13, 2023, a policy paper authored by Israel’s Ministry of Intelligence was leaked. It recommended “the forcible and permanent transfer of the Gaza Strip’s 2.2 million Palestinian residents to Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula,” as +972 reported. The paper laid out three possible scenarios for the people of Gaza. The first involves the replacement of Hamas with the Palestinian Authority in Gaza. The second involves the emergence of a new local Gaza authority (not Hamas or PA), and the third includes the expulsion of all civilians into Egypt. The report clearly identifies the third scenario as the most preferable option. The report’s authors write that this third option “will yield positive, long-term strategic outcomes for Israel, and is an executable option. It requires determination from the political echelon in the face of international pressure, with an emphasis on harnessing the support of the United States and additional pro-Israeli countries for the endeavor.” Of course, US support for moving Gazans into the Sinai Peninsula began literally minutes after October 7. This would create a serious problem for future retaliation by extremely radicalized and traumatized people whose families have been killed by Israel’s crimes for decades. Perhaps if this was still 1996, and no powerful coalition of Russia, China, and Iran existed to defend Egypt against the threatened Anglo-Zionist war, then the PNAC Clean Break: A Strategy for Securing the Realm might be possible. The decision to ignore reality by rehashing this obsolete program implies the height of incompetence, which threatens to grow far beyond a regional war and into a global thermonuclear conflagration more quickly than many imagine. This foreshadowing of a prophetic global war to usher in the Messiah (as many Christian rapturists dream of) was outlined in depth by Greater Israel advocate and Jabotinsky collaborator Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook 100 years ago. Kook was Britain’s selection for the Chief Ashkenaz Rabbi for Jerusalem and Palestine from 1919 to 1935, and his influence in shaping several generations of radical Zionist zealots that took over control of much of Israel’s government after the inside job that was the Six Day War is immense. His prophetic remarks should not be easily dismissed. In his book Orot, Kook said: “In wars, national characters crystalize. Israel, as the universal reflection of mankind, benefits thereby. The heels of Messiah follow upon World Conflagration… At the hour of the downfall of Western civilization, Israel is called upon to fulfill its divine mission by providing the spiritual basis for a New World Order.” [emphasis added] The only hope to avoid this calamity and disrupt this flight toward an Armageddon scenario steered by End Times Messianic cultists is to force a ceasefire, as Russia, China, and the vast majority of world citizens (even Americans) demand. Without this restoration of sanity, the world as a whole will be in for an experience that will make the 14th-century Dark Age appear to be an uncomfortable hiccup in world history. Bio: I am the editor-in-chief of The Canadian Patriot Review, Senior Fellow of the American University in Moscow and Director of the Rising Tide Foundation. I’ve written the four volume Untold History of Canada series, four volume Clash of the Two Americas series, the Revenge of the Mystery Cult Trilogy and Science Unshackled: Restoring Causality to a World in Chaos. I am also co-host of the weekly Breaking History on Badlands Media and host of Pluralia Dialogos (which airs every second Sunday at 11am ET here). This article was first published on Pluralia Follow my work on Telegram at: T.me/CanadianPatriotPress

|

writingdate

Dating, Relationships & Stories

Monday, March 9, 2026

Greater Israel Forces a Chaotic Realignment of Global Systems

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Greater Israel Forces a Chaotic Realignment of Global Systems

In 1996, a nest of American-born imperialists revolving around Paul Wolfowitz, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and Richard Perle created a new...

-

Greetings everyone ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Rising Tide Foundation cross-posted a post from Matt Ehret's Insights Rising Tide Foundation Sep 25 · Rising Tide Foundation Come see M...

-

March 16 at 2pm Eastern Time ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...